Well in english all words include vowels and you are excluding every vowel except u and (sometimes) y

scrabble fan?

Tone of article suggests this is some sort of friendly gift but friends don't give friends pagers. Employers give workers pagers. How did Donald Trump accept a gift that seems to symbolize he's on call? Why hasn't he tweeted a picture of it dropped in a toilet or something?

And are we thinking either the gold pager or the real pager is a bomb and/or listening device? so weird

Let's properly cite that:

Shrestha, M.B., Shrestha, G., Dangaura, H.L., Chaudhary, R., Shrestha, P.M., Dewan, K., Sada, R., Savage, M., and Zuofu Xiang (2025). Confirmation of the Presence of Asian Small-Clawed Otter Aonyx cinereus in Nepal after 185 Years. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 42 (1): 3 – 8

And here is the text of the "short note", but the original contains images, references, links and translation which I've removed:

Volume 42 Issue 1 (January 2025)

Citation: Shrestha, M.B., Shrestha, G., Dangaura, H.L., Chaudhary, R., Shrestha, P.M., Dewan, K., Sada, R., Savage, M., and Zuofu Xiang (2025). Confirmation of the Presence of Asian Small-Clawed Otter Aonyx cinereus in Nepal after 185 Years. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 42 (1): 3 – 8

Confirmation of the Presence of Asian Small-Clawed Otter Aonyx cinereus in Nepal after 185 Years.

Mohan Bikram Shrestha1*, Ganga Shrestha2, Hiru Lal Dangaura3, Rajeev Chaudhary4, Purna Man Shrestha2, Karun Dewan5, Rajesh Sada5, Melissa Savage6, and Zuofu Xiang1

_1College of Forestry, Soil and Water Conservation, Central South University of Forestry and Technology, Changsha, Hunan, China

2Wildlife Research and Education Network, Tokha, Kathmandu, Nepal

3Bird Conservation Nepal, Lazimpat, Kathmandu, Nepal

4Division Forest Office, Dadeldhura, Nepal

5WWF-Nepal

6University of California, USA

*Corresponding Author Email: shrmohan5@gmail.com

Received 1st December 2024, accepted 5th December 2024

Abstract: The Asian Small-clawed Otter has not been observed in Nepal since 1839. Because of a lack of evidence of the species over such a prolonged period, it has been sometimes suggested that it is extinct in the country. Here, we present the first photographic evidence of Asian Small-clawed Otter in Nepal in 185 years. In November 2024, a juvenile Asian Small-clawed Otter was captured at the confluence of Rangun Khola and Puntara Khola of Dadeldhura District in far-western Nepal, was nurtured in the Forest Office for a week before released to the wild. The presence of a juvenile otter implies the presence of other otter individuals in the area. This rare observation is a significant confirmation of the species presence in Nepal and warrants detailed study and conservation initiatives to conserve the species.

Keywords: Asian Small-clawed Otter, rediscovery, Rangun Khola, Puntara Khola, Nepal

INTRODUCTION

Nepal has been said to be home to three species of otters, smooth-coated otter (Lutrogale perspicillata), Eurasian Otter (Lutra lutra) and Asian Small-clawed Otter (Aonyx cinereus) (Acharya and Rajbhandari, 2011). Confirmed evidence for the presence of Small-clawed Otters in Nepal has been lacking since the mid-19th century. The Asian Small-clawed Otter was last reported by Hodgson in 1939 (Hodgson, 1839). The Smooth-coated Otter has been the most studied Otter species of Nepal. Studies on Eurasian Otter is gaining momentum in recent years. The species’ status was ambiguous for decades till was observed in the Barekot, Roshi and Tubang Rivers (Shrestha et al., 2021), in the Pelma River (Shrestha et al., 2022) and in area of Kathmandu Valley (Shrestha et al., 2023). In contrast, Asian Small-clawed Otter have not been recorded in Nepal; for more than a century and a half since 1839 (Acharya et al., 2023). Only anecdotal records from Nepal were in from Makalu Barun National Park, Kailali and Kapilvastu Districts (Jnawali et al., 2011). Globally categorized by the IUCN as Vulnerable (Wright et al., 2021) and listed as Data deficient species in National Red List Assessment of Mammals of Nepal (Jnawali et al., 2011). Deficient information on Asian Small-clawed Otter made its status in Nepal indeterminate (Jnawali et al., 2011).

OTTER SIGHTING SITE AND SPECIES IDENTIFICATION

In November 2024, a juvenile Asian Small-clawed Otter was sighted at the river junction of the Rangun Khola and its feeder stream the Puntara Khola at Parsuram Municipality-12 of Dadeldhura District in far-western Nepal (29.132819˚N 80.335374˚ E; 401m asl) (Fig. 1). Downstream, the Rangun Khola flows into the Mahakali River (also called as Sarada River) and then into the Karnali River in India.

Figure 1. Location map of Asian Small-clawed Otter capture.

Morphological characteristics and species identification of the otter in photographs and videos confirmed as an Asian Small-clawed Otter by IUCN Otter Specialist Group members (Fig. 2). The species has front paws with reduced nails, well adapted for catching small vertebrate and invertebrate prey in shallow and murky water (Hussain et al., 2011; Nicole Duplaix, pers. comm.). The juvenile otter was captured by a local, transferred to the nearby Sub-division Forest Office and nurtured for a week before released to the wild. The Forest Officer (co-author) shared photographs and videos with otter researchers in Nepal (primary author) for species identification, which was further forwarded to IUCN Otter Specialist Group members for the confirmation.

Figure 2. Asian Small-clawed Otter (Photograph: Rajeev Chaudary)

HABITAT NOTE

A brief habitat study was carried out 1-km upstream and downstream from the otter sighting location as a baseline for future study. The habitat characterstics of four sites were noted: the otter observation location, 1-km upstream at the Rangun Khola and at feeder stream the Puntara Khola, and 1-km downstream in the Rangun Khola (Fig. 3). The location of the otter sighting was close to the human settlements Katar and Jogbudha. The bank-to-bank river width varied from 235-750m, but the river itself was shrunken due to the marked reduction of post-monsoon flow, with a tranquil flow and shallow depth. The riverbank was composed of large stones (˃10cm-0.5m), small stones (1-10cm) and sand and mud with higher cover of large stones. The bank vegetation cover was sparse with small patches of Imperata cylindrica and Chromolaena odorata. The otter was observed at the edge of leasehold forest, where mining of stone and sand, washing, bathing and fishing activities were common.

Figure 3. Sites of Asian Small-clawed Otter observation site (red circle) and habitat studies (green circle).

CONCLUSION

The sighting of an Asian Small-clawed Otter after 185 years is a remarkable discovery for conservation in Nepal, ending concerns that the species may have been extinct in the country. The sighting highlights the need for detailed study of the status of this species in Nepal and urgent implementation of conservation initiatives. Small-scale mining of construction materials from local rivers, primarily the Puntara Khola is likely to increase in the near future, with substantial impact on aquatic life. The traditional fishing practices using net casting, fishing hooks, draining water, and trapping fish in rice paddies are common. Besides, fishing using poison and explosives have been increasing. These activities will cause a decline in fish populations. Deforestation, habitat degradation, overgrazing, non-point source pollution and agricultural run-off are additional threats to the aquatic life in the area. There are five micro-hydro plants in the Rangun Khola with impacts to the aquatic biodiversity (USAID, 2018). Otters are resilient to highly modified anthropogenic landscapes (Lee, 1996; Theng and Sivasothi, 2016), flexible in habitat selection (Aadrean et al., 2010; Weinberger et al., 2016) and able to recover from low numbers (Marcelli and Fusillo, 2009; Uscamaita and Bodmer, 2010). Nevertheless, given the rare occurrence of Small-clawed Otter in Nepal, mitigation measures are urgently needed for conservation of the species int this region. National otter survey, scientific studies of ecology and phylogeny of the species and conservation measures at priority sites are called for. Nepal has shown an exemplary effort in the conservation of megafauna, resulting in significant population increases of species such as rhinoceros and tigers. A timely conservation effort for this exceptionally rare species, a keystone aquatic mesocarnivore is now urgently needed in Nepal.

Acknowledgments - Authors are grateful to the Sub-Division Forest Office and Division Forest Office of Dadeldhura for their support providing data. We are grateful to residents of Jogbudha and Katar, Dadeldhura for further information. We thank Nicole Duplaix, IUCN Otter Specialist Group Co-chair for the identification of the Asian Small-clawed Otter from photographs and videos.

Country Joe & the Fish: Feeling Like I'm Fixin To Die Rag

currently working invidious: https://inv.nadeko.net/watch?v=ft0vkKCadgk

even as a kid I though the "F U C K" part at the beginning was kind of corny.

Anyone else love some baby boomer shit? When I was growing up it was the only role model available of people who had fought against the American state, the status quo, capitalism, imperialism, etc. And you got the vague impression they won even if the details weren't too clear and it seemed like all these things were still happening.

AVN declined to comment, but last week, it launched a FAQ page for attendees of the event. “The hotel has assured us that the strike will not impact the AVN Expo and Awards. Contingency measures are in place to maintain a memorable guest experience and exceptional service during the event,” the page says.

On January 9, the Adult Performance Artists Guild (APAG) issued a statement about the strike: “As the union for performers in the adult industry, care for the safety and well-being of our workers is paramount to our mission,” they wrote. “We feel this for not only our members and other workers in the adult industry but for all workers, regardless of their jobs. As union representatives, we support the sacrifices made by workers on strike, fighting for better working conditions. The officers of APAG voted unanimously to support our fellow union workers in Culinary Workers Local 226, and we will not cross their picket line in a show of solidarity.”

And on Saturday, marking day 58 of the strike, APAG members joined Local 226 workers and their families for a march from the Las Vegas Strip to Virgin Hotels, blaring vuvuzelas and holding signs referencing Virgin Las Vegas’ contract negotiation offer of an estimated 30 cents an hour in wage increases.

“The Adult Performance Artists Guild (APAG)’s decision to stand with Culinary Union strikers and honor the picket line at Virgin Las Vegas demonstrates unity, and the Culinary Union applauds the unwavering solidarity shown by the APAG and their members,” Ted Pappageorge, Secretary-Treasurer for the Culinary Union, said in a statement. “Workers across industries share the same fight for dignity, fair pay, respect, and protections on-the-job, and Culinary Union is proud to stand with APAG in solidarity as strikers continue to take on a billionaire-owned company that refuses to treat workers fairly. APAG’s support sends a powerful message: When workers stand together, we are unstoppable. To APAG members and all customers choosing not to cross the picket line – thank you for standing with workers on strike, with your continued support we will win.”

Anyone watched it? Is it good?

I'm halfway through the first episode and it is looking pretty OK.

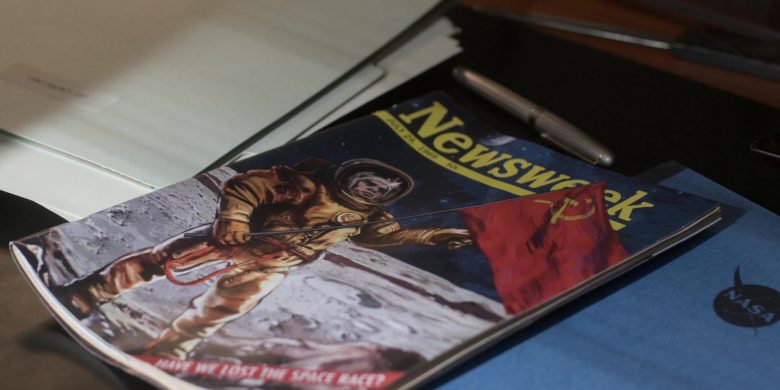

Premise

In an alternate timeline in 1969, Soviet cosmonaut Alexei Leonov becomes the first human to land on the Moon. This outcome devastates morale at NASA but also catalyzes a U.S. effort to catch up. With the Soviet Union emphasizing diversity by including a woman in subsequent landings, the United States is forced to match pace, training women and minorities who were largely excluded from the initial decades of U.S. space exploration. Each subsequent season takes place 10 years later, with season two taking place in the 1980s, season three taking place in the 1990s, and season four taking place in the 2000s.

In one of the many ironies of an autocratic Chinese state built on an official ideology of communism but funded by unbridled capitalism, Xiaohongshu shares the same name as the book of Mao Zedong’s writings that became a symbol of the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s and 70s.

The “red” of that title referred to leftist ideology, but the modern-day “red” is a reference to hot fashions and trends. Perhaps the only things the two red books share are their wild popularity at home and fears about their impact beyond China’s border.

Young social media users said they rarely see overt Chinese propaganda, and that occasional clumsy attempts to promote their neighbour at Taiwan’s expense are more likely to make them laugh than change their politics. “You just have to be aware, and it will be OK [using Chinese apps],” said Lo, the student artist who mostly uses two obscure apps, Bilibili and Lofter.

“We saw one Taiwanese celebrity interviewed on Chinese state media, saying: ‘The seafood in China is so good – we don’t have that in Taiwan.’ We just thought it was funny,” she added. Taiwan, surrounded by rich fishing grounds, is famous for its cuisine, including seafood.

Politicians and experts say this kind of heavy-handed messaging is not their main concern. They fear content on the apps carries subtle messages about language and culture which attempt to deny or even erase the existence of a Taiwanese national and cultural identity.

“The Chinese Communist party wants Taiwanese people to love Chinese culture,” said Wang, the educator. “They hope that by convincing the students or young people to agree on the culture, it can help them agree on Chinese politics and government … maybe convince the Taiwanese students that we are all Chinese.”

‘Into brain and the heart’: how China is using apps to woo Taiwan’s teenagers

Lifestyle and shopping apps are the latest weapons in Beijing’s information war against its neighbour

Emma Graham-Harrison and Chi-hui Lin in Taichung

Sun 13 Aug 2023 10.00 CEST

Ariel Lo spends a couple of hours most weeks sharing anime art and memes on Chinese apps, often chatting with friends in China in a Mandarin slightly different from the one she uses at home in Taiwan.

“People use English on Instagram, and for Chinese apps they use Chinese phrases. If I am talking to friends in China, I would use them,” Lo said as she picked up a bubble tea at a street market in central Taichung city.

The 18-year-old Earth sciences student, who creates art in her spare time, is part of a generation whose online life is increasingly influenced by content from China. That is worrying politicians and experts who fear young Taiwanese drawn to shop and entertain themselves on apps ultimately controlled by Beijing may be getting more than style tips, and sharing more than memes.

Social media companies can harvest valuable data and shape perspectives through the algorithms that control what posts viewers see. The FBI last year warned that TikTok and its Chinese counterpart, Douyin. were a threat to national security.

In Taiwan, those worries are particularly acute. China has made clear that it wants to take control of Taiwan, by force if necessary; and the two share a common language. That makes Chinese apps, music and drama particularly attractive and accessible to the Taiwanese and Taiwanese users a particularly important audience for Beijing.

“The similarities in language make the risk higher,” said Josh Wang of the Taiwan Pang-phuann Association of Education, which is building an education programme to make Taiwanese students more aware of online risks and how to protect themselves. “Students in Taiwan don’t necessarily care much about politics, so when it comes to finding entertainment, it’s convenient and easy to [use Chinese apps].”

He sees the influence of those shows, songs and memes spreading in Taiwan in the way that young people speak. Lo may restrict her use of phrases from China to chats on the apps, but others are sounding more like teenagers across the Taiwan Strait. “For example, my own students start using language in daily life like niubi [a popular Chinese slang word equating to ‘super cool’],” said Wang.

The two Chinese apps that are most popular in Taiwan are Douyin – the Chinese version of TikTok, run by the same parent company, ByteDance – and Xiaohongshu, or “little red book”, a lifestyle and social shopping site dubbed the “Chinese Instagram”.

In December last year, the Taiwanese government barred public sector employees from using TikTok and Xiaohongshu on official phones and other devices.

“Taiwan is the frontline of China’s information war,” said Chui Chih-Wei, a lawmaker from Taiwan’s ruling Democratic Progressive party, who wants to see the government ban matched by the private sector to protect Taiwan’s economy.

“It is impossible to ban these apps entirely as we are a democratic country, but today we already see the first small success. Now we should encourage big companies in Taiwan to ban it – ones linked to national security, to energy,” he said. “It takes time to get big firms behind something like this.”

Cultural influence is a relatively new concern for Taiwan. Decades ago, it was a style and culture beacon for China as the country struggled out of Maoist drabness and conformity, looking to icons like the Taiwanese singer Teresa Teng and the director Ang Lee. Now, older Taiwanese watch Chinese historical dramas and soap operas, and the younger generation is hooked on apps.

The Taiwanese government is worried about teenagers using TikTok and its Chinese version, Douyin. Photograph: Social Media

Scarlett Ling is a firm supporter of Taiwanese independence, and a heavy user of Douyin. “I am so bored, I use it every day for over two hours,” the 16-year-old admitted as she browsed a market in central Taichung city with a friend.

She worries about her data being siphoned off to servers controlled by Beijing, and refuses requests for her ID number. But the Chinese app has “better filters”, and she insists she steers clear of politics anyway. “I am just using it for lifestyle inspiration ... I certainly can’t be influenced [about politics].”

Rochelle Hsieh, a 21-year-old business logistics student snapping pictures of possible outfits in a Taipei clothes shop, said she gets much of her inspiration from Xiaohongshu, and spends two or three hours a day on there and Instagram.

In one of the many ironies of an autocratic Chinese state built on an official ideology of communism but funded by unbridled capitalism, Xiaohongshu shares the same name as the book of Mao Zedong’s writings that became a symbol of the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s and 70s.

The “red” of that title referred to leftist ideology, but the modern-day “red” is a reference to hot fashions and trends. Perhaps the only things the two red books share are their wild popularity at home and fears about their impact beyond China’s border.

Young social media users said they rarely see overt Chinese propaganda, and that occasional clumsy attempts to promote their neighbour at Taiwan’s expense are more likely to make them laugh than change their politics. “You just have to be aware, and it will be OK [using Chinese apps],” said Lo, the student artist who mostly uses two obscure apps, Bilibili and Lofter.

“We saw one Taiwanese celebrity interviewed on Chinese state media, saying: ‘The seafood in China is so good – we don’t have that in Taiwan.’ We just thought it was funny,” she added. Taiwan, surrounded by rich fishing grounds, is famous for its cuisine, including seafood.

Politicians and experts say this kind of heavy-handed messaging is not their main concern. They fear content on the apps carries subtle messages about language and culture which attempt to deny or even erase the existence of a Taiwanese national and cultural identity.

“The Chinese Communist party wants Taiwanese people to love Chinese culture,” said Wang, the educator. “They hope that by convincing the students or young people to agree on the culture, it can help them agree on Chinese politics and government … maybe convince the Taiwanese students that we are all Chinese.”

Beijing has described its propaganda strategy for Taiwan as “into the island, into the household, into the brain, into the heart”, an approach that clearly aims to exploit popular culture, sociologist Wang Horng-Luen wrote in a recent article about China’s soft-power influence.

Thinking that China is the root of culture will loosen the foundation of Taiwan’s sense of community

Wang Horng-Luen

A professor at the sociology department of the National Taiwan University, he said that Chinese content can reinforce colonial narratives that erase or minimise Taiwanese identity and culture. “Thinking that China is the root of culture ... will indeed loosen the foundation of Taiwan’s sense of community,” he wrote. It may also lead to “blind worship and dependence on China”.

Students spend on average five hours a day online, outside of class, and more than two-thirds say they get most of their news and information from the internet, Wang’s team working on social media education found. Media literacy classes are compulsory, but schools have not kept pace with student lives. Nearly nine out of 10 students think they have seen false information online, but two-thirds never or rarely used fact checking.

“The education system requires media literacy classes, but teachers have no idea how to teach it,” Wang said. “They teach how to read a newspaper with a critical perspective. But the students don’t read newspapers.”

he is the worst regular in all of the treks I have seen (TOS/TNG/DS9/VOY/ENT)

his whole thing is representing White american baby boomer dudes

boring as shit

doesn't belong in space

Torres can do so much better.

I don't believe this shit about being such a hot shot pilot.

I think he was sent by the CIA.

when I was making my previous post, the suggestion box thingy that pops up listed this one from 2023. It had this cute image I thought deserved resharing.

On Wednesday 29 June 2022, we began calling on all FOSS developers to give up on GitHub.

We realize this is not an easy task; GitHub is ubiquitous. Through their effective marketing, GitHub has convinced Free and Open Source Software (FOSS) developers that GitHub is the best (and even the only) place for FOSS development. However, as a proprietary, trade-secret tool, GitHub itself is the very opposite of FOSS. By contrast, Git was designed specifically to replace a proprietary tool (BitKeeper), and to make FOSS development distributed — using FOSS tools and without a centralized site. GitHub has warped Git — creating add-on features that turn a distributed, egalitarian, and FOSS system into a centralized, proprietary site. And, all those add-on features are controlled by a single, for-profit company. By staying on GitHub, established FOSS communities bring newcomers to this proprietary platform — expanding GitHub's reach. and limiting the imaginations of the next generation of FOSS developers.

We know that many rely on GitHub every day. Giving up a ubiquitous, gratis service that has useful (albeit proprietary) features is perennially difficult. For software developers, giving up GitHub will be even harder than giving up Facebook! We don't blame anyone who struggles, but hope you will read the reasons and methods below to give up GitHub and join us in seeking better alternatives! Also, please check back to this page regularly, as we'll continue to update it throughout 2022 and beyond!

There are so many reasons to give up on GitHub, but we list here a few of the most important ones:

Copilot is a for-profit product — developed and marketed by Microsoft and their GitHub subsidiary — that uses Artificial Intelligence (AI) techniques to automatically generate code interactively for developers. The AI model was trained (according to GitHub's own statements) exclusively with projects that were hosted on GitHub, including many licensed under copyleft licenses. Most of those projects are not in the “public domain”, they are licensed under FOSS licenses. These licenses have requirements including proper author attribution and, in the case of copyleft licenses, they sometimes require that works based on and/or that incorporate the software be licensed under the same copyleft license as the prior work. Microsoft and GitHub have been ignoring these license requirements for more than a year. Their only defense of these actions was a tweet by their former CEO, in which he falsely claims that unsettled law on this topic is actually settled. In addition to the legal issues, the ethical implications of GitHub's choice to use copylefted code in the service of creating proprietary software are grave.

In 2020, the community discovered that GitHub has a for-profit software services contract with the USA Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). Activists, including some GitHub employees, have been calling on GitHub for two years to cancel that contract. GitHub's primary reply has been that their parent company, Microsoft, has sold Microsoft Word for years to ICE without any public complaints. They claim that this somehow justifies even more business with an agency whose policies are problematic. Regardless of your views on ICE and its behavior, GitHub's ongoing dismissive and disingenuous responses to the activists who raised this important issue show that GitHub puts its profits above concerns from the community.

While GitHub pretends to be pro-FOSS (like SourceForge before them), their entire hosting site is, itself, proprietary and/or trade-secret software. We appreciate that GitHub allows some of its employees to sometimes contribute FOSS to upstream projects, but our community has been burned so many times before by companies that claim to support FOSS, while actively convincing the community to rely on their proprietary software. We won't let GitHub burn us in this same way!

GitHub differs from most of its peers in the FOSS project hosting industry, as GitHub does not even offer any self-hosting FOSS option. Their entire codebase is secret. For example, while we have our complaints about GitLab's business model of parallel “Community” and “Enterprise” editions, at least GitLab's Community Edition provides basic functionality for self-hosting and is 100% FOSS. Meanwhile, there are non-profit FOSS hosting sites such as CodeBerg, who develop their platform publicly as FOSS.

GitHub has long sought to discredit copyleft generally. Their various CEOs have often spoken loudly and negatively about copyleft, including their founder (and former CEO) devoting his OSCON keynote on attacking copyleft and the GPL. This trickled down from the top. We've personally observed various GitHub employees over the years arguing in many venues to convince projects to avoid copyleft; we've even seen a GitHub employee do this in a GitHub bug ticket directly.

GitHub is wholly owned by Microsoft, a company whose executives have historically repeatedly attacked copyleft licensing.

The reason that it's difficult to leave GitHub is a side-effect of one of the reasons to leave them: proprietary vendor lock-in. We are aware that GitHub, as the “Facebook of software development”, has succeeded in creating the most enticing walled garden ever made for FOSS developers. Just like leaving Facebook is painful because you're unsure how you'll find and talk with your friends and family otherwise — leaving GitHub is difficult because it's how you find and collaborate with co-developers. GitHub may even be how you find and showcase your work to prospective employers. We also know that some Computer Science programs even require students to use GitHub.

Accordingly, we call first on the most comfortably-situated developers among you — leaders of key FOSS projects, hiring and engineering managers, and developers who are secure in their employment — to take the first step to reject GitHub's proprietary services. We recognize that for new developers in the field, you'll receive pressure from potential employers (even those that will otherwise employ you to develop FOSS) to participate on GitHub. Collective action requires the privileged developers among us to lead by example; that's why we're not merely asking you leave GitHub, but we're spearheading an effort to help everyone give up GitHub over the long term. You can help protect newcomers from the intrinsic power imbalance created by GitHub by setting the agenda for your FOSS project and hosting your project elsewhere.

As such, we're speaking first to the hiring managers, community leaders, and those in other positions of power that encourage the use of GitHub to new contributors and existing communities. Once someone in power makes the choice to host a project on GitHub, the individual contributors have little choice but to use these proprietary and damaging products. If you are making decisions or have political power within your community and/or employer, we urge you to use your power to center community efforts through FOSS platforms rather than GitHub. If you're an individual contributor who feels powerless to leave GitHub, read our (growing) list of recommendations below on how to take the first steps.

Long term, we'll develop this stable URL (that can always be reached by GiveUpGitHub.org) to include links to resources to help everyone — from the most privileged developer to newcomers and members of underrepresented groups in FOSS — to give up on GitHub. If you don't feel that you or your project can yet leave GitHub, we ask that you raise awareness by adding this section to your README.md to share your concerns about GitHub with your users. If you're ready to leave GitHub, you can use this README.md template to replace your current one.

千里之行始於足下

The journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step.

— 老子 (Lao Tsu) in Chapter 64 of 道德经 (Tao Te Ching)

Here are some resources to help you quit GitHub. We'll be expanding this list regularly as we find more resources. If you'd like to suggest a resource not yet listed, you can discuss it on the Give-Up-GitHub mailing list.

Here are some ideas of how you can help raise the importance of this issue even while you're still a GitHub user. (We'll publish longer tutorials in future about these and other ways to help.)

Add this section to your README.md to share your concerns about GitHub with your users.

Respectfully and kindly ask, before you contribute to a project on GitHub, if they could provide alternative means to contribute other than using GitHub.

Explain to your employer the dangers of relying on GitHub's proprietary vendor lock-in products.

Join the give-up-github mailing list and start threads about your difficulties leaving GitHub. This will help us explore solutions with you and add material to this page.

Jo Freeman, the original author, has posted this on her website with some intro:

The earliest version of this article was given as a talk at a conference called by the Southern Female Rights Union, held in Beulah, Mississippi in May 1970. It was written up for Notes from the Third Year (1971), but the editors did not use it. It was then submitted to several movement publications, but only one asked permission to publish it; others did so without permission. The first official place of publication was in Vol. 2, No. 1 of The Second Wave (1972). This early version in movement publications was authored by Joreen. Different versions were published in the Berkeley Journal of Sociology, Vol. 17, 1972-73, pp. 151-165, and Ms. magazine, July 1973, pp. 76-78, 86-89, authored by Jo Freeman. This piece spread all over the world. Numerous people have edited, reprinted, cut, and translated "Tyranny" for magazines, books and web sites, usually without the permission or knowledge of the author. The version below is a blend of the three cited here.

Original text, taken from redsails because the formatting was friendlier

During the years in which the women’s liberation movement has been taking shape, a great emphasis has been placed on what are called leaderless, structureless groups as the main — if not sole — organizational form of the movement. The source of this idea was a natural reaction against the over-structured society in which most of us found ourselves, and the inevitable control this gave others over our lives, and the continual elitism of the Left and similar groups among those who were supposedly fighting this overstructuredness.

The idea of “structurelessness,” however, has moved from a healthy counter to those tendencies to becoming a goddess in its own right. The idea is as little examined as the term is much used, but it has become an intrinsic and unquestioned part of women’s liberation ideology. For the early development of the movement this did not much matter. It early defined its main goal, and its main method, as consciousness-raising, and the “structureless” rap group was an excellent means to this end. The looseness and informality of it encouraged participation in discussion, and its often supportive atmosphere elicited personal insight. If nothing more concrete than personal insight ever resulted from these groups, that did not much matter, because their purpose did not really extend beyond this.

The basic problems didn’t appear until individual rap groups exhausted the virtues of consciousness-raising and decided they wanted to do something more specific. At this point they usually foundered because most groups were unwilling to change their structure when they changed their tasks. Women had thoroughly accepted the idea of “structurelessness” without realizing the limitations of its uses. People would try to use the “structureless” group and the informal conference for purposes for which they were unsuitable out of a blind belief that no other means could possibly be anything but oppressive.

If the movement is to grow beyond these elementary stages of development, it will have to disabuse itself of some of its prejudices about organization and structure. There is nothing inherently bad about either of these. They can be and often are misused, but to reject them out of hand because they are misused is to deny ourselves the necessary tools to further development. We need to understand why “structurelessness” does not work.

Contrary to what we would like to believe, there is no such thing as a structureless group. Any group of people of whatever nature that comes together for any length of time for any purpose will inevitably structure itself in some fashion. The structure may be flexible; it may vary over time; it may evenly or unevenly distribute tasks, power and resources over the members of the group. But it will be formed regardless of the abilities, personalities, or intentions of the people involved. The very fact that we are individuals, with different talents, predispositions, and backgrounds makes this inevitable. Only if we refused to relate or interact on any basis whatsoever could we approximate structurelessness — and that is not the nature of a human group.

This means that to strive for a structureless group is as useful, and as deceptive, as to aim at an “objective” news story, “value-free” social science, or a “free” economy. A “laissez faire” group is about as realistic as a “laissez faire” society; the idea becomes a smokescreen for the strong or the lucky to establish unquestioned hegemony over others. This hegemony can be so easily established because the idea of “structurelessness” does not prevent the formation of informal structures, only formal ones. Similarly “laissez faire” philosophy did not prevent the economically powerful from establishing control over wages, prices, and distribution of goods; it only prevented the government from doing so. Thus structurelessness becomes a way of masking power, and within the women’s movement is usually most strongly advocated by those who are the most powerful (whether they are conscious of their power or not). As long as the structure of the group is informal, the rules of how decisions are made are known only to a few and awareness of power is limited to those who know the rules. Those who do not know the rules and are not chosen for initiation must remain in confusion, or suffer from paranoid delusions that something is happening of which they are not quite aware.

For everyone to have the opportunity to be involved in a given group and to participate in its activities the structure must be explicit, not implicit. The rules of decision-making must be open and available to everyone, and this can happen only if they are formalized. This is not to say that formalization of a structure of a group will destroy the informal structure. It usually doesn’t. But it does hinder the informal structure from having predominant control and make available some means of attacking it if the people involved are not at least responsible to the needs of the group at large. “Structurelessness” is organizationally impossible. We cannot decide whether to have a structured or structureless group, only whether or not to have a formally structured one. Therefore the word will not be used any longer except to refer to the idea it represents. Unstructured will refer to those groups which have not been deliberately structured in a particular manner. Structured will refer to those which have. A Structured group always has formal structure, and may also have an informal, or covert, structure. It is this informal structure, particularly in Unstructured groups, which forms the basis for elites.

“Elitist” is probably the most abused word in the women’s liberation movement. It is used as frequently, and for the same reasons, as “pinko” was used in the fifties. It is rarely used correctly. Within the movement it commonly refers to individuals, though the personal characteristics and activities of those to whom it is directed may differ widely: An individual, as an individual can never be an elitist, because the only proper application of the term “elite” is to groups. Any individual, regardless of how well-known that person may be, can never be an elite.

Correctly, an elite refers to a small group of people who have power over a larger group of which they are part, usually without direct responsibility to that larger group, and often without their knowledge or consent. A person becomes an elitist by being part of, or advocating the rule by, such a small group, whether or not that individual is well known or not known at all. Notoriety is not a definition of an elitist. The most insidious elites are usually run by people not known to the larger public at all. Intelligent elitists are usually smart enough not to allow themselves to become well known; when they become known, they are watched, and the mask over their power is no longer firmly lodged.

Elites are not conspiracies. Very seldom does a small group of people get together and deliberately try to take over a larger group for its own ends. Elites are nothing more, and nothing less, than groups of friends who also happen to participate in the same political activities. They would probably maintain their friendship whether or not they were involved in political activities; they would probably be involved in political activities whether or not they maintained their friendships. It is the coincidence of these two phenomena which creates elites in any group and makes them so difficult to break.

These friendship groups function as networks of communication outside any regular channels for such communication that may have been set up by a group. If no channels are set up, they function as the only networks of communication. Because people are friends, because they usually share the same values and orientations, because they talk to each other socially and consult with each other when common decisions have to be made, the people involved in these networks have more power in the group than those who don’t.

And it is a rare group that does not establish some informal networks of communication through the friends that are made in it.

Some groups, depending on their size, may have more than one such informal communications network. Networks may even overlap. When only one such network exists, it is the elite of an otherwise Unstructured group, whether the participants in it want to be elitists or not. If it is the only such network in a Structured group it may or may not be an elite depending on its composition and the nature of the formal Structure. If there are two or more such networks of friends, they may compete for power within the group, thus forming factions, or one may deliberately opt out of the competition, leaving the other as the elite. In a Structured group, two or more such friendship networks usually compete with each other for formal power. This is often the healthiest situation, as the other members are in a position to arbitrate between the two competitors for power and thus to make demands on those to whom they give their temporary allegiance.

The inevitably elitist and exclusive nature of informal communication networks of friends is neither a new phenomenon characteristic of the women’s movement nor a phenomenon new to women. Such informal relationships have excluded women for centuries from participating in integrated groups of which they were a part. In any profession or organization these networks have created the “locker room” mentality and the “old school” ties which have effectively prevented women as a group (as well as some men individually) from having equal access to the sources of power or social reward. Much of the energy of past women’s movements has been directed to having the structures of decision-making and the selection processes formalized so that the exclusion of women could be confronted directly. As we well know, these efforts have not prevented the informal male-only networks from discriminating against women, but they have made it more difficult.

Because elites are informal does not mean they are invisible. At any small group meeting anyone with a sharp eye and an acute ear can tell who is influencing whom. The members of a friendship group will relate more to each other than to other people. They listen more attentively, and interrupt less; they repeat each other’s points and give in amiably; they tend to ignore or grapple with the “outs” whose approval is not necessary for making a decision. But it is necessary for the “outs” to stay on good terms with the “ins.” Of course the lines are not as sharp as I have drawn them. They are nuances of interaction, not prewritten scripts. But they are discernible, and they do have their effect. Once one knows with whom it is important to check before a decision is made, and whose approval is the stamp of acceptance, one knows who is running things.

Since movement groups have made no concrete decisions about who shall exercise power within them, many different criteria are used around the country. Most criteria are along the lines of traditional female characteristics. For instance, in the early days of the movement, marriage was usually a prerequisite for participation in the informal elite. As women have been traditionally taught, married women relate primarily to each other, and look upon single women as too threatening to have as close friends. In many cities, this criterion was further refined to include only those women married to New Left men. This standard had more than tradition behind it, however, because New Left men often had access to resources needed by the movement — such as mailing lists, printing presses, contacts, and information — and women were used to getting what they needed through men rather than independently. As the movement has charged through time, marriage has become a less universal criterion for effective participation, but all informal elites establish standards by which only women who possess certain material or personal characteristics may join. They frequently include: middle-class background (despite all the rhetoric about relating to the working class); being married; not being married but living with someone; being or pretending to be a lesbian; being between the ages of twenty and thirty; being college educated or at least having some college background; being “hip”; not being too “hip”; holding a certain political line or identification as a “radical”; having children or at least liking them; not having children; having certain “feminine” personality characteristics such as being “nice”; dressing right (whether in the traditional style or the antitraditional style); etc. There are also some characteristics which will almost always tag one as a “deviant” who should not be related to. They include: being too old; working full time, particularly if one is actively committed to a “career”; not being “nice”; and being avowedly single (i.e., neither actively heterosexual nor homosexual).

Other criteria could be included, but they all have common themes. The characteristics prerequisite for participating in the informal elites of the movement, and thus for exercising power, concern one’s background, personality, or allocation of time. They do not include one’s competence, dedication to feminism, talents, or potential contribution to the movement. The former are the criteria one usually uses in determining one’s friends. The latter are what any movement or organization has to use if it is going to be politically effective.

The criteria of participation may differ from group to group, but the means of becoming a member of the informal elite if one meets those criteria art pretty much the same. The only main difference depends on whether one is in a group from the beginning, or joins it after it has begun. If involved from the beginning it is important to have as many of one’s personal friends as possible also join. If no one knows anyone else very well, then one must deliberately form friendships with a select number and establish the informal interaction patterns crucial to the creation of an informal structure. Once the informal patterns are formed they act to maintain themselves, and one of the most successful tactics of maintenance is to continuously recruit new people who “fit in.” One joins such an elite much the same way one pledges a sorority. If perceived as a potential addition, one is “rushed” by the members of the informal structure and eventually either dropped or initiated. If the sorority is not politically aware enough to actively engage in this process itself it can be started by the outsider pretty much the same way one joins any private club. Find a sponsor, i.e., pick some member of the elite who appears to be well respected within it, and actively cultivate that person’s friendship. Eventually, she will most likely bring you into the inner circle.

All of these procedures take time. So if one works full time or has a similar major commitment, it is usually impossible to join simply because there are not enough hours left to go to all the meetings and cultivate the personal relationship necessary to have a voice in the decision-making. That is why formal structures of decision making are a boon to the overworked person. Having an established process for decision-making ensures that everyone can participate in it to some extent.

Although this dissection of the process of elite formation within small groups has been critical in perspective, it is not made in the belief that these informal structures are inevitably bad — merely inevitable. All groups create informal structures as a result of interaction patterns among the members of the group. Such informal structures can do very useful things But only Unstructured groups are totally governed by them. When informal elites are combined with a myth of “structurelessness,” there can be no attempt to put limits on the use of power. It becomes capricious.

This has two potentially negative consequences of which we should be aware. The first is that the informal structure of decision-making will be much like a sorority — one in which people listen to others because they like them and not because they say significant things. As long as the movement does not do significant things this does not much matter. But if its development is not to be arrested at this preliminary stage, it will have to alter this trend. The second is that informal structures have no obligation to be responsible to the group at large. Their power was not given to them; it cannot be taken away. Their influence is not based on what they do for the group; therefore they cannot be directly influenced by the group. This does not necessarily make informal structures irresponsible. Those who are concerned with maintaining their influence will usually try to be responsible. The group simply cannot compel such responsibility; it is dependent on the interests of the elite.

The idea of “structurelessness” has created the “star” system. We live in a society which expects political groups to make decisions and to select people to articulate those decisions to the public at large. The press and the public do not know how to listen seriously to individual women as women; they want to know how the group feels. Only three techniques have ever been developed for establishing mass group opinion: the vote or referendum, the public opinion survey questionnaire, and the selection of group spokespeople at an appropriate meeting. The women’s liberation movement has used none of these to communicate with the public. Neither the movement as a whole nor most of the multitudinous groups within it have established a means of explaining their position on various issues. But the public is conditioned to look for spokespeople.

While it has consciously not chosen spokespeople, the movement has thrown up many women who have caught the public eye for varying reasons. These women represent no particular group or established opinion; they know this and usually say so. But because there are no official spokespeople nor any decision-making body that the press can query when it wants to know the movement’s position on a subject, these women are perceived as the spokespeople. Thus, whether they want to or not, whether the movement likes it or not, women of public note are put in the role of spokespeople by default.

This is one main source of the ire that is often felt toward the women who are labeled “stars.” Because they were not selected by the women in the movement to represent the movement’s views, they are resented when the press presumes that they speak for the movement. But as long as the movement does not select its own spokeswomen, such women will be placed in that role by the press and the public, regardless of their own desires.

This has several negative consequences for both the movement and the women labeled “stars.” First, because the movement didn’t put them in the role of spokesperson, the movement cannot remove them. The press put them there and only the press can choose not to listen. The press will continue to look to “stars” as spokeswomen as long as it has no official alternatives to go to for authoritative statements from the movement. The movement has no control in the selection of its representatives to the public as long as it believes that it should have no representatives at all. Second, women put in this position often find themselves viciously attacked by their sisters. This achieves nothing for the movement and is painfully destructive to the individuals involved. Such attacks only result in either the woman leaving the movement entirely-often bitterly alienated — or in her ceasing to feel responsible to her “sisters.” She may maintain some loyalty to the movement, vaguely defined, but she is no longer susceptible to pressures from other women in it. One cannot feel responsible to people who have been the source of such pain without being a masochist, and these women are usually too strong to bow to that kind of personal pressure. Thus the backlash to the “star” system in effect encourages the very kind of individualistic nonresponsibility that the movement condemns. By purging a sister as a “star,” the movement loses whatever control it may have had over the person who then becomes free to commit all of the individualistic sins of which she has been accused.

Unstructured groups may be very effective in getting women to talk about their lives; they aren’t very good for getting things done. It is when people get tired of “just talking” and want to do something more that the groups flounder, unless they change the nature of their operation. Occasionally, the developed informal structure of the group coincides with an available need that the group can fill in such a way as to give the appearance that an Unstructured group “works.” That is, the group has fortuitously developed precisely the kind of structure best suited for engaging in a particular project.

While working in this kind of group is a very heady experience, it is also rare and very hard to replicate. There are almost inevitably four conditions found in such a group;

While these conditions can occur serendipitously in small groups, this is not possible in large ones. Consequently, because the larger movement in most cities is as unstructured as individual rap groups, it is not too much more effective than the separate groups at specific tasks. The informal structure is rarely together enough or in touch enough with the people to be able to operate effectively. So the movement generates much motion and few results. Unfortunately, the consequences of all this motion are not as innocuous as the results’ and their victim is the movement itself.

Some groups have formed themselves into local action projects if they do not involve many people and work on a small scale. But this form restricts movement activity to the local level; it cannot be done on the regional or national. Also, to function well the groups must usually pare themselves down to that informal group of friends who were running things in the first place. This excludes many women from participating. As long as the only way women can participate in the movement is through membership in a small group, the nongregarious are at a distinct disadvantage. As long as friendship groups are the main means of organizational activity, elitism becomes institutionalized.

For those groups which cannot find a local project to which to devote themselves, the mere act of staying together becomes the reason for their staying together. When a group has no specific task (and consciousness raising is a task), the people in it turn their energies to controlling others in the group. This is not done so much out of a malicious desire to manipulate others (though sometimes it is) as out of a lack of anything better to do with their talents. Able people with time on their hands and a need to justify their coming together put their efforts into personal control, and spend their time criticizing the personalities of the other members in the group. Infighting and personal power games rule the day. When a group is involved in a task, people learn to get along with others as they are and to subsume personal dislikes for the sake of the larger goal. There are limits placed on the compulsion to remold every person in our image of what they should be.

The end of consciousness-raising leaves people with no place to go, and the lack of structure leaves them with no way of getting there. The women the movement either turn in on themselves and their sisters or seek other alternatives of action. There are few that are available. Some women just “do their own thing.” This can lead to a great deal of individual creativity, much of which is useful for the movement, but it is not a viable alternative for most women and certainly does not foster a spirit of cooperative group effort. Other women drift out of the movement entirely because they don’t want to develop an individual project and they have found no way of discovering, joining, or starting group projects that interest them.

Many turn to other political organizations to give them the kind of structured, effective activity that they have not been able to find in the women’s movement. Those political organizations which see women’s liberation as only one of many issues to which women should devote their time thus find the movement a vast recruiting ground for new members. There is no need for such organizations to “infiltrate” (though this is not precluded). The desire for meaningful political activity generated in women by their becoming part of the women’s liberation movement is sufficient to make them eager to join other organizations when the movement itself provides no outlets for their new ideas and energies. Those women who join other political organizations while remaining within the women’s liberation movement, or who join women’s liberation while remaining in other political organizations, in turn become the framework for new informal structures. These friendship networks are based upon their common nonfeminist politics rather than the characteristics discussed earlier, but operate in much the same way. Because these women share common values, ideas, and political orientations, they too become informal, unplanned, unselected, unresponsible elites — whether they intend to be so or not.

These new informal elites are often perceived as threats by the old informal elites previously developed within different movement groups. This is a correct perception. Such politically oriented networks are rarely willing to be merely “sororities” as many of the old ones were, and want to proselytize their political as well as their feminist ideas. This is only natural, but its implications for women’s liberation have never been adequately discussed. The old elites are rarely willing to bring such differences of opinion out into the open because it would involve exposing the nature of the informal structure of the group.

Many of these informal elites have been hiding under the banner of “anti-elitism” and “structurelessness.” To effectively counter the competition from another informal structure, they would have to become “public,” and this possibility is fraught with many dangerous implications. Thus, to maintain its own power, it is easier to rationalize the exclusion of the members of the other informal structure by such means as “red-baiting,” “reformist-baiting,” “lesbian-baiting,” or “straight-baiting.” The only other alternative is to formally structure the group in such a way that the original power structure is institutionalized. This is not always possible. If the informal elites have been well structured and have exercised a fair amount of power in the past, such a task is feasible. These groups have a history of being somewhat politically effective in the past, as the tightness of the informal structure has proven an adequate substitute for a formal structure. Becoming Structured does not alter their operation much, though the institutionalization of the power structure does open it to formal challenge. It is those groups which are in greatest need of structure that are often least capable of creating it. Their informal structures have not been too well formed and adherence to the ideology of “structurelessness” makes them reluctant to change tactics. The more Unstructured a group is, the more lacking it is in informal structures, and the more it adheres to an ideology of “structurelessness,” the more vulnerable it is to being taken over by a group of political comrades.

Since the movement at large is just as Unstructured as most of its constituent groups, it is similarly susceptible to indirect influence. But the phenomenon manifests itself differently. On a local level most groups can operate autonomously; but the only groups that can organize a national activity are nationally organized groups. Thus, it is often the Structured feminist organizations that provide national direction for feminist activities, and this direction is determined by the priorities of those organizations. Such groups as NOW, WEAL, and some leftist women’s caucuses are simply the only organizations capable of mounting a national campaign. The multitude of Unstructured women’s liberation groups can choose to support or not support the national campaigns, but are incapable of mounting their own. Thus their members become the troops under the leadership of the Structured organizations. The avowedly Unstructured groups have no way of drawing upon the movement’s vast resources to support its priorities. It doesn’t even have a way of deciding what they are.

The more unstructured a movement it, the less control it has over the directions in which it develops and the political actions in which it engages. This does not mean that its ideas do not spread. Given a certain amount of interest by the media and the appropriateness of social conditions, the ideas will still be diffused widely. But diffusion of ideas does not mean they are implemented; it only means they are talked about. Insofar as they can be applied individually they may be acted on; insofar as they require coordinated political power to be implemented, they will not be.

As long as the women’s liberation movement stays dedicated to a form of organization which stresses small, inactive discussion groups among friends, the worst problems of Unstructuredness will not be felt. But this style of organization has its limits; it is politically inefficacious, exclusive, and discriminatory against those women who are not or cannot be tied into the friendship networks. Those who do not fit into what already exists because of class, race, occupation, education, parental or marital status, personality, etc., will inevitably be discouraged from trying to participate. Those who do fit in will develop vested interests in maintaining things as they are.

The informal groups’ vested interests will be sustained by the informal structures which exist, and the movement will have no way of determining who shall exercise power within it. If the movement continues deliberately to not select who shall exercise power, it does not thereby abolish power. All it does is abdicate the right to demand that those who do exercise power and influence be responsible for it. If the movement continues to keep power as diffuse as possible because it knows it cannot demand responsibility from those who have it, it does prevent any group or person from totally dominating. But it simultaneously insures that the movement is as ineffective as possible. Some middle ground between domination and ineffectiveness can and must be found.

These problems are coming to a head at this time because the nature of the movement is necessarily changing. Consciousness-raising as the main function of the women’s liberation movement is becoming obsolete. Due to the intense press publicity of the last two years and the numerous overground books and articles now being circulated, women’s liberation has become a household word. Its issues are discussed and informal rap groups are formed by people who have no explicit connection with any movement group. The movement must go on to other tasks. It now needs to establish its priorities, articulate its goals, and pursue its objectives in a coordinated fashion. To do this it must get organized — locally, regionally, and nationally.

Once the movement no longer clings tenaciously to the ideology of “structurelessness,” it is free to develop those forms of organization best suited to its healthy functioning. This does not mean that we should go to the other extreme and blindly imitate the traditional forms of organization. But neither should we blindly reject them all. Some of the traditional techniques will prove useful, albeit not perfect; some will give us insights into what we should and should not do to obtain certain ends with minimal costs to the individuals in the movement. Mostly, we will have to experiment with different kinds of structuring and develop a variety of techniques to use for different situations. The Lot System is one such idea which has emerged from the movement. It is not applicable to all situations, but is useful in some. Other ideas for structuring are needed. But before we can proceed to experiment intelligently, we must accept the idea that there is nothing inherently bad about structure itself — only its excess use.

While engaging in this trial-and-error process, there are some principles we can keep in mind that are essential to democratic structuring and are also politically effective:

When these principles are applied, they insure that whatever structures are developed by different movement groups will be controlled by and responsible to the group. The group of people in positions of authority will be diffuse, flexible, open, and temporary. They will not be in such an easy position to institutionalize their power because ultimate decisions will be made by the group at large. The group will have the power to determine who shall exercise authority within it.

Obligations of Israel in relation to the presence and activities of the United Nations, other international organizations and third States in and in relation to the Occupied Palestinian Territory

(Request for advisory opinion)

No. 196 23 December 2024

ORDER

The President of the International Court of Justice,

Having regard to Articles 48, 65 and 66 of the Statute of the Court and to Articles 103, 104 and 105 of the Rules of Court;

Whereas on 19 December 2024 the United Nations General Assembly adopted, at the 54th meeting of its Seventy-Ninth Session, resolution 79/232, by which it decided, in accordance with Article 96 of the Charter of the United Nations, to request the International Court of Justice, pursuant to Article 65 of the Statute of the Court, to render an advisory opinion;

Whereas certified true copies of the English and French texts of that resolution were transmitted to the Court under cover of a letter from the Secretary-General of the United Nations dated 20 December 2024 and received on 23 December 2024; Whereas paragraph 10 of this resolution reads as follows:

“The General Assembly,

........

\10. Decides, in accordance with Article 96 of the Charter of the United Nations, to request the International Court of Justice, pursuant to Article 65 of the Statute of the Court, on a priority basis and with the utmost urgency, to render an advisory opinion on the following question, considering the rules and principles of international law, as regards in particular the Charter of the United Nations, international humanitarian law, international human rights law, privileges and immunities applicable under international law for international organizations and States, relevant resolutions of the Security Council, the General Assembly and the Human Rights Council, the advisory opinion of the Court of 9 July 2004, and the advisory opinion of the Court of 19 July 2024, in which the Court reaffirmed the duty of an occupying Power to administer occupied territory for the benefit of the local population and affirmed that Israel is not entitled to sovereignty over or to exercise sovereign powers in any part of the Occupied Palestinian Territory on account of its occupation:

What are the obligations of Israel, as an occupying Power and as a member of the United Nations, in relation to the presence and activities of the United Nations, including its agencies and bodies, other international organizations and third States, in and in relation to the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including to ensure and facilitate the unhindered provision of urgently needed supplies essential to the survival of the Palestinian civilian population as well as of basic services and humanitarian and development assistance, for the benefit of the Palestinian civilian population, and in support of the Palestinian people’s right to self-determination?”;

Whereas the Secretary-General indicated in his letter that, pursuant to Article 65, paragraph 2, of the Statute, all documents likely to throw light upon the question would be transmitted to the Court in due course; Whereas, by letters dated 23 December 2024, the Registrar gave notice of the request for an advisory opinion to all States entitled to appear before the Court, pursuant to Article 66, paragraph 1, of the Statute; Whereas, in view of the fact that the General Assembly has requested that the advisory opinion of the Court be rendered “on a priority basis and with the utmost urgency”, it is incumbent upon the Court to take all necessary steps to accelerate the procedure, as contemplated by Article 103 of its Rules,

Decides that the United Nations and its Member States, as well as the observer State of Palestine, are considered likely to be able to furnish information on the question submitted to the Court for an advisory opinion and may do so within the time-limits fixed in this Order;

Fixes 28 February 2025 as the time-limit within which written statements on the question may be presented to the Court, in accordance with Article 66, paragraph 2, of the Statute; and

Reserves the subsequent procedure for further decision.

Done in French and in English, the French text being authoritative, at the Peace Palace, The Hague, this twenty-third day of December, two thousand and twenty-four. (Signed) Nawaf SALAM, President. (Signed) Philippe GAUTIER, Registrar.

PDF original: Order of 23 December 2024 - 196-20241223-ord-01-00-en.pdf

ETA: I believe this case is separate from Legal Consequences arising from the Policies and Practices of Israel in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem.

video is about 6 mins long. in case you know anyone who's on the fence.

Source: Amnesty concludes Israel is committing genocide in Gaza

Listen to an audio version of this article.

I first heard about ghost artists in the summer of 2017. At the time, I was new to the music-streaming beat. I had been researching the influence of major labels on Spotify playlists since the previous year, and my first report had just been published. Within a few days, the owner of an independent record label in New York dropped me a line to let me know about a mysterious phenomenon that was “in the air” and of growing concern to those in the indie music scene: Spotify, the rumor had it, was filling its most popular playlists with stock music attributed to pseudonymous musicians—variously called ghost or fake artists—presumably in an effort to reduce its royalty payouts. Some even speculated that Spotify might be making the tracks itself. At a time when playlists created by the company were becoming crucial sources of revenue for independent artists and labels, this was a troubling allegation.

At first, it sounded to me like a conspiracy theory. Surely, I thought, these artists were just DIY hustlers trying to game the system. But the tips kept coming. Over the next few months, I received more notes from readers, musicians, and label owners about the so-called fake-artist issue than about anything else. One digital strategist at an independent record label worried that the problem could soon grow more insidious. “So far it’s happening within a genre that mostly affects artists at labels like the one I work for, or Kranky, or Constellation,” the strategist said, referring to two long-running indie labels.* “But I doubt that it’ll be unique to our corner of the music world for long.”

By July, the story had burst into public view, after a Vulture article resurfaced a year-old item from the trade press claiming that Spotify was filling some of its popular and relaxing mood playlists—such as those for “jazz,” “chill,” and “peaceful piano” music—with cheap fake-artist offerings created by the company. A Spotify spokesperson, in turn, told the music press that these reports were “categorically untrue, full stop”: the company was not creating its own fake-artist tracks. But while Spotify may not have created them, it stopped short of denying that it had added them to its playlists. The spokesperson’s rebuttal only stoked the interest of the media, and by the end of the summer, articles on the matter appeared from NPR and the Guardian, among other outlets. Journalists scrutinized the music of some of the artists they suspected to be fake and speculated about how they had become so popular on Spotify. Before the year was out, the music writer David Turner had used analytics data to illustrate how Spotify’s “Ambient Chill” playlist had largely been wiped of well-known artists like Brian Eno, Bibio, and Jon Hopkins, whose music was replaced by tracks from Epidemic Sound, a Swedish company that offers a subscription-based library of production music—the kind of stock material often used in the background of advertisements, TV programs, and assorted video content.

For years, I referred to the names that would pop up on these playlists simply as “mystery viral artists.” Such artists often had millions of streams on Spotify and pride of place on the company’s own mood-themed playlists, which were compiled by a team of in-house curators. And they often had Spotify’s verified-artist badge. But they were clearly fake. Their “labels” were frequently listed as stock-music companies like Epidemic, and their profiles included generic, possibly AI-generated imagery, often with no artist biographies or links to websites. Google searches came up empty.

In the years following that initial salvo of negative press, other controversies served as useful distractions for Spotify: the company’s 2019 move into podcasting and eventual $250 million deal with Joe Rogan, for example, and its 2020 introduction of Discovery Mode, a program through which musicians or labels accept a lower royalty rate in exchange for algorithmic promotion. The fake-artist saga faded into the background, another of Spotify’s unresolved scandals as the company increasingly came under fire and musicians grew more emboldened to speak out against it with each passing year.

Then, in 2022, an investigation by the Swedish daily Dagens Nyheter revived the allegations. By comparing streaming data against documents retrieved from the Swedish copyright collection society STIM, the newspaper revealed that around twenty songwriters were behind the work of more than five hundred “artists,” and that thousands of their tracks were on Spotify and had been streamed millions of times.

Around this time, I decided to dig into the story of Spotify’s ghost artists in earnest, and the following summer, I made a visit to the DN offices in Sweden. The paper’s technology editor, Linus Larsson, showed me the Spotify page of an artist called Ekfat. Since 2019, a handful of tracks had been released under this moniker, mostly via the stock-music company Firefly Entertainment, and appeared on official Spotify playlists like “Lo-Fi House” and “Chill Instrumental Beats.” One of the tracks had more than three million streams; at the time of this writing, the number has surpassed four million. Larsson was amused by the elaborate artist bio, which he read aloud. It described Ekfat as a classically trained Icelandic beat maker who graduated from the “Reykjavik music conservatory,” joined the “legendary Smekkleysa Lo-Fi Rockers crew” in 2017, and released music only on limited-edition cassettes until 2019. “Completely made up,” Larsson said. “This is probably the most absurd example, because they really tried to make him into the coolest music producer that you can find.”

Besides the journalists at DN, no one in Sweden wanted to talk about the fake artists. In Stockholm, I visited the address listed for one of the ghost labels and knocked on the door—no luck. I met someone who knew a guy who maybe ran one of the production companies, but he didn’t want to talk. A local businessman would reveal only that he worked in the “functional music space,” and clammed up as soon as I told him about my investigation.

Even with the new reporting, there was still much missing from the bigger picture: Why, exactly, were the tracks getting added to these hugely popular Spotify playlists? We knew that the ghost artists were linked to certain production companies, and that those companies were pumping out an exorbitant number of tracks, but what was their relationship to Spotify?

For more than a year, I devoted myself to answering these questions. I spoke with former employees, reviewed internal Spotify records and company Slack messages, and interviewed and corresponded with numerous musicians. What I uncovered was an elaborate internal program. Spotify, I discovered, not only has partnerships with a web of production companies, which, as one former employee put it, provide Spotify with “music we benefited from financially,” but also a team of employees working to seed these tracks on playlists across the platform. In doing so, they are effectively working to grow the percentage of total streams of music that is cheaper for the platform. The program’s name: Perfect Fit Content (PFC). The PFC program raises troubling prospects for working musicians. Some face the possibility of losing out on crucial income by having their tracks passed over for playlist placement or replaced in favor of PFC; others, who record PFC music themselves, must often give up control of certain royalty rights that, if a track becomes popular, could be highly lucrative. But it also raises worrying questions for all of us who listen to music. It puts forth an image of a future in which—as streaming services push music further into the background, and normalize anonymous, low-cost playlist filler—the relationship between listener and artist might be severed completely.