The Fall Of The King

Peter Brixtofte and The Neoliberal Welfare Utopia

In early February 2002, the town of Farum radiated confident optimism. Just twenty kilometres north of Copenhagen, nestled between two picturesque lakes and connected to the capital by a commuter train line, Farum was a middle class Utopia for its roughly 18,000 residents.

Children strolled to school carrying not heavy backpacks, but brand-new laptops, a gift from the municipality. Pensioners prepared for their annual holidays in the Mediterranean, all expenses paid by city hall. These weren’t elite privileges, but public services, available to everyone. Remarkably, it wasn’t funded by soaring taxes: Farum boasted some of the lowest tax rates in the country.

Unemployment seemed a distant specter, kept at bay by a pioneering workfare scheme. Those seeking benefits were required to pack goods for private companies or attend intensive Danish language classes. Naysayers and killjoys on the left decried it as "slave labor," renting out citizens without proper rights, but official numbers showed that it worked. Public buildings shone with newness. Dominating the skyline was Farum Park, a striking 10,000-seat football stadium capable of seating half the town, a monument to civic ambition. Down by the lakeside, a new marina added a touch of prosperity. The local football team, Farum BK, fueled by municipal ambition and generous private sponsorships, was on the cusp of qualifying for Denmark’s top professional league after a meteoric rise. Everywhere one looked, things in Farum seemed fresher, brighter, and more generous than they had any right to be.

At the heart of this glittering vision stood Peter Brixtofte. Charismatic, tireless, and impossible to ignore, he was the mastermind behind Farum’s transformation. The right-wing press affectionately called him “Denmark’s worst-dressed politician,” a nod to his perpetually ill-fitting suits, a quirk that only seemed to enhance his everyman appeal. Brixtofte made himself accessible, seemingly knowing every resident by name, always ready to cut through red tape or call in favors from his vast personal network. If someone needed a permit, a job or even a bicycle, he could make it happen. Mayor for over a decade, wielding an absolute majority on the council, Brixtofte appeared to have cracked the code of municipal governance. His potent blend of tax-cutting, privatization, and lavish public services, the "Farum Model", was hailed as visionary, copied by other right-wing councils, and championed nationally by his own Liberal Party as the blueprint for the welfare state of the new millennium. Farum wasn’t just successful; it felt like a triumphant refutation of the old, lingering social democratic welfare state, proof that liberals were the true, efficient stewards of the future.

But beneath the shine, something was off. There was a tension in the air – a sense that the dream was too perfect, too frictionless. And as the old saying goes: if it seems too good to be true, it probably is. Farum was living in a dream. A harsh awakening was in the making

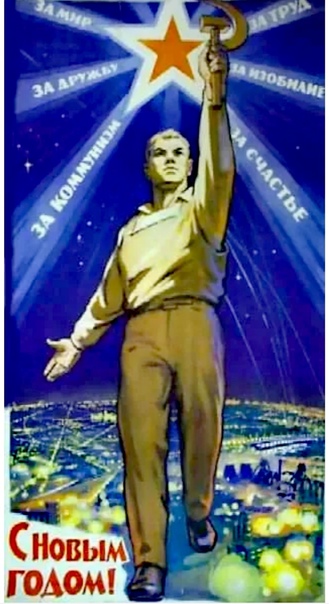

- Peter Brixtofte (left) wearing a mayoral chain and Thor Pedersen (right) wearing sunglasses at the opening of Farum's new city hall in 1989

A Liberal Wunderkind

Peter Brixtofte was born on December 11, 1949, in Copenhagen, the son of a civil servant. When his father landed an administrative job at NATO, the family followed along and for four years the young Brixtofte attended the Lycée Internationale d’OTAN in Paris, an exclusive school for the children of NATO bureaucrats. The experience left a deep impression. Surrounded by classmates from across the world, Brixtofte absorbed a cosmopolitan worldview and developed a distaste for nationalism and xenophobia that would later set him apart from Denmark’s increasingly xenophobic political mainstream. Later in life, he described his time “among Frenchmen, Americans, Chinese, [soft N-word redacted]” as transformative. His personal experience of language unlocking French society became the bedrock for his later insistence on mandatory Danish classes for unemployed immigrants, a policy masking its coercive edge as integration.

While his brother Jens pursued a musical career, winning Denmark’s Eurovision contest in 1982, only to place second to last internationally, Peter turned to politics. After earning a political science degree from the University of Copenhagen in 1972 at the age of 22, the youngest graduate to ever do that. He entered parliament just a year later. During the 1980s, as xenophobic rhetoric began creeping into Danish public life, Brixtofte remained aligned with the political mainstream which had not yet been infected. He warned that failing to engage with immigrant communities risked fostering “national self-satisfaction bordering on nationalism,” and argued that Danes could learn from immigrants, particularly in matters of family values. This early stance would later contrast starkly with the viciously racist policies of his party under Anders Fogh Rasmussen.

Brixtofte’s true power base, however, was Farum. Elected to the local council in 1979, his breakthrough came on election night in 1985. Although the Liberals had won just 5 of 21 seats, Brixtofte outmanoeuvred the Social Democrats by rejecting their offer of the mayoralty in exchange for all committee chairs. Instead he struck a deal with the Socialist People’s Party (SF) and Farum’s lone Communist councillor, securing the mayor’s chain for himself. The communist, incidentally, would later defect and join the Liberal Party.

By 1989, the Liberals had won an outright majority. Brixtofte ruled unopposed.

Once in power, he moved fast. Inspired by the prevailing winds of Thatcherite and Reaganite neoliberalism, Brixtofte cut taxes, outsourced public services, and declared war on bureaucracy. City Hall staff plummeted from 220 full-time employees when he took office to a skeletal 55 by the time he left. Early results seemed miraculous: finances improved, and at the opening of a gleaming new City Hall 1989, Liberal Party Interior Minister Thor Pedersen praised Farum as a "model municipality." A new cultural center followed in 1992.

Brixtofte ruled Farum as his personal petty kingdom. Dissent was not tolerated. He cultivated a court of loyalists, appointing people without relevant experience or education to key positions, often people he had helped out of trouble, ensuring their dependence. Those who crossed him faced demotion, salary cuts, or dismissal.

In 1994 the municipally employed psychologist Ulla Andersen gave a sarcastic speech at a farewell reception for the latest victim of Brixtofte's leadership style, the town's fourth municipal director over a period of just eight years. She spoke ironically about the mayor's love of power and prestige. Paraphrasing the fairytale about The Emperor's New Clothes she said: "It makes no sense, they thought. But they didn't say it. For those who couldn't see the brilliance in the mayor's ideas were either unfit for their office or unforgivably stupid". Many people laughed. Brixtofte was not one of them. The infuriated mayor fired her on the spot. Though later forced to retract the dismissal, he subjected her to unbearable workloads until she resigned. During the ensuing legal battle, which the city lost, city hall made the extraordinary claim that mocking the mayor was just as serious an offense as physically assaulting him would be.

A cornerstone of Brixtofte’s early "success" was his aggressive workfare scheme. Benefit claimants were compelled into menial labor for private companies or language classes under threat of losing their benefits. An agreement between the union SiD and Farum in the 1980s meant that the unemployed in workfare were required to join unions and unemployment insurance funds. For the union it was about labour rights, for Brixtofte it was a cynical cost-shifting ploy. Farum would keep the workers in employment for a year before firing them, just enough for them to qualify for state-funded unemployment insurance payouts rather than municipally funded benefits. Brixtofte would openly boast about this strategy in media interviews.

SiD railed against the workfare scheme, accusing Farum of renting out the unemployed as cheap labor without rights, while companies reaped the benefits. In 1992, SiD took legal action, complaining about abuse of citizens in the workfare scheme. The municipality would rent them out to private businesses. The companies paid union wages to Farum, which then paid the workers unemployment benefits and pocketed the difference. SiD likened it to slave labour. The case failed. The county oversight committee and a labour arbitration court was convinced by the municipality's claims that the arrangement was a work capability assessment scheme and not employment.

In 1993 Jydsk Rengøring, the company in which Thor Pedersen had become CEO after leaving government, was awarded a contract on cleaning services at a retirement home. As part of the agreement they had been handed a large amount of benefit claimants who were formally undergoing a training programme but who were in reality working for Jydsk Rengøring. Although the unemployment schemes in Farum were notoriously opaque, it is clear that the scheme was a huge financial benefit for the company.

Though often lauded by the right as being the solution to unemployment, later analysis found that the claimed workfare miracle in Farum was built on hype and questionable statistics. Employment is driven by demand, not supply and in reality, Farum did no better or no worse than other municipalities when it came to fighting unemployment.

Brixtofte’s true financial wizardry, however, was the infamous "Farum Model", a sale and lease-back scheme. Starting as early as 1990, he began selling off municipal assets, the roads and parks department, the municipal sewer system, even retirement homes, to private investors, only to lease them back on long-term contracts. Loopholes in Denmark’s tax code made the deals lucrative for both sides, generating large upfront windfalls for the town. Critics said it shifted costs onto taxpayers in other parts of the country. Brixtofte brushed them aside.

In 1992, tax minister Anders Fogh Rasmussen resigned over a “creative bookkeeping” scandal. Brixtofte replaced him while continuing to run Farum as a side hustle but his time in government was short-lived. The conservative/liberal coalition of Poul Schlüter collapsed in 1993 as a consequence of a legal scandal in which minister of justice Erik Ninn Hansen criminally refused asylum to Tamil refugees despite them being entitled to it.

In 1995, Brixtofte was knighted, cementing his national stature.

His ambition grew stronger. In the mid-1990s, Brixtofte set his eyes on the leadership of the Liberal Party, positioning himself as successor to Uffe Ellemann-Jensen. His main rival was the shrewd Anders Fogh Rasmussen. The battle turned vicious. During the 1990’s and early 2000’s, persistent rumors about Anders Fogh Rasmussen allegedly being a closeted homosexual whispered through the public as well as the halls of parliament. Frequently politicians and journalists, including ministers in the ruling Social Democratic/Social Liberal coalition would joke among themselves about his alleged gay relationships. It was exactly the kind of thing people loved to believe about the robotic and uptight Anders Fogh Rasmussen.

While Brixtofte always denied responsibility, the near-universal belief within the political elite, including the leadership of the Liberal Party, was that he was the source of the rumours. Although many made jokes, few people seriously believed the gossip and the claims failed to hurt Anders Fogh Rasmussen politically. The homophobic smear campaign backfired and when Ellemann-Jensen stepped down in 1998, Anders Fogh Rasmussen secured the leadership. Brixtofte was sidelined, his national career was over. Embittered, he turned his energies entirely towards consolidating his power in Farum where he was still the big fish, determined to build his kingdom there.

The Kingdom of Farum

Brixtofte ruled over Farum unchallenged. Power was executed not in the council chamber but in the taproom of a local inn, unofficially dubbed "Committee Room Number Eight". There Brixtofte, presiding over his court of yes-men, would map out Farum's future over fine food and expensive wine. After the opening of Farum Park stadium in 1999, Brixtofte would move the proceedings to Restaurant Sepp, located there. Liberal Party group meetings would often feature food and wine paid for by the city. Under Brixtofte, Farum’s spending on “representation” ballooned, eclipsing neighboring towns by a factor of twenty.

Behind the charismatic public facade, a profound darkness festered. Brixtofte had developed a severe alcohol dependency. His daughter Maria later recalled the emotional toll: the unease of watching their father spiral, the unsettling transformation from the energetic, sober man of the morning to the distant, intoxicated figure who returned each evening. While his daughters also recalled moments of joy, dancing to Jewish folk music in the morning, being introduced to a broad cultural diet spanning from French cinema to folk comedies and football, even Sunday visits to the local Turkish cultural association, a highly unusual activity for an ethnically Danish family at the time, the alcoholism was a corrosive constant.

At city hall, the effects were visible. Brixtofte grew increasingly autocratic and paranoid, especially following his exit from national politics in 1998.

Financially, the kingdom was built on sand. The initial cash bonanza from selling off municipal assets fueled Brixtofte’s megalomaniacal construction projects and expansive welfare services. Beyond the legendary laptops and pensioner holidays, came guaranteed childcare, new housing projects for students and the elderly, and, above all, his obsession: Farum BK, the local football club forged in a merger of two smaller clubs, engineered by Brixtofte in 1992. Convinced Farum could host a Champions League club, he poured municipal resources into the team, becoming a major shareholder and chairman. Many Liberal councillors also held shares. Brixtofte was hellbent on making Farum Denmark's sports capital, hiring professional athletes as coaches and consultants. The stadium, Farum Park, and the adjacent Farum Arena stood as glittering monuments to his ambition. The new marina completed the picture.

Warnings were there for anyone willing to look. But few wanted to. Nationally, the “Farum Model” remained political gold. The Liberal Party, eager to shed its 1980s image as heartless libertarian cave-men and appeal to a broader electorate of welfare-loving Danes, the party pointed to Farum as proof liberals could deliver a generous, efficient welfare state. Lars Løkke Rasmussen, then mayor of the Frederiksborg County which Farum was part of, and himself a rising star, was a fervent admirer. He copied Brixtofte’s sale-leaseback scheme, selling a psychiatric hospital, praising the model as "a dynamic interplay of the public and private sectors" delivering "more service and more choices for the same money." As late as January 2002, the national Liberal Party lauded Farum as "an exemplary reform municipality," highlighting twelve years of tax cuts alongside free laptops and pensioner vacations as proof of what liberals could achieve in local politics.

But within Farum, the cracks were widening. Critics described a toxic political culture of opaque deals and vicious personal attacks. Helene Lund, an SF councillor with over a decade on the council, was one of the few who dared to oppose him. In a 1999 article she stated plainly: "I think he is mean. When we have a meeting I never know where the attacks will come from but I can be sure they'll come. And by the way the attacks are never of a political nature as I experience it." She fought a losing battle against Brixtofte’s tactic of moving most decisions from public agendas to closed sessions, a practice that intensified after 1998. Public council meetings became brief, meaningless formalities, with one regular attendant remarking that they were so short that it was hardly worth the trouble to take your jacket off when attending. Brixtofte attempted to cut the number of council meetings to just six a year but was stopped by the county's oversight commission.

An atmosphere of fear prevailed; several councillors reported being watched when reviewing documents at city hall and they were afraid to bring anything home, suspecting documents were marked to trace leaks, a tactic Brixtofte had used before. An anonymous councillor spoke of the "hell" that awaited anyone who dared challenge him publicly. The local branch of the liberal party dismissed the accusations as baseless and accused the smaller parties on the council for being mad that they could never vote anything through.

Inside the planning department, officials resented how anyone with a plot of land and a Farum BK sponsorship contract could get a planning permit. One official who refused to alter a critical note on a student housing project received what city hall employees called "the mushroom treatment": sent to a dark place and covered in shit, while more compliant colleagues were ordered to make the edits.

Brixtofte chafed against any constraint. In 2000, furious at how the National Municipal Association worked against his sale and lease back schemes, he withdrew Farum entirely. He refused an Interior Ministry directive to post 600 million DKK (RMB 672 mln.) as collateral for sports facility construction. In 2001, he ignored an environmental board order to halt the illegal construction of student housing in a designated industrial zone.

His next grand scheme was about to take off in the summer of 2002: transforming a decommissioned military base into a massive new neighborhood. The project would drastically expand Farum’s population and, Brixtofte believed, its tax base. The vision was bold but the foundations of his kingdom were already crumbling.

- Peter Brixtofte in his heyday

Downfall

On February 6, 2002 the tabloid B.T. detonated the first bomb: "Drank for DKK 150,000 in a day" (RMB 168,000). A few weeks before, a terrified anonymous city hall employee had snuck up the garden path to the home of journalist Morten Pihl under the cover of night. "I've never been here." was his first words to the journalist "You've never spoken to me. It must never be made public. I have never been here. You must promise me that!" Only once Pihl had agreed to the terms of silence did the man confirm what the journalist suspected, the plastic bag full of receipts from Restaurant Sepp that the table had been handed by an unknown source was authentic.

The B.T. story detailed astronomical spending on "representation," centered on Restaurant Sepp, owned by Farum BK. One receipt showed a single bill for 63,027 DKK (RMB 70,592), 61,440 DKK (RMB 68.822) of it for just eight bottles of wine for Brixtofte and four guests, fraudulently expensed as payment for "30 full-day seminars."

On February 7 B.T. struck again. Brixtofte had inexplicably delayed payment on a municipal property purchase, gifting the seller, a friend of Brixtofte, 325,000 DKK (RMB 364,000) in late fees. That afternoon, Helene Lund and other councillors filed police reports against the mayor. Brixtofte dismissed the unfolding scandal as nothing more than a politically motivated witch hunt and promptly announced a three-month leave from both the mayor’s office and parliament.

In the evening, the police questioned Jørn Frederiksen, the city’s former Technical Director, on the property deal. But while the authorities moved in, so did Brixtofte’s people. His chief of staff, Sten Gensmann, slipped into Frederiksen’s office and began removing large amounts of files about municipal property deals. Unbeknownst to Gensmann, the police had already seized the files related to the scandalous property deal. Gensmann had not acted alone; he’d been sent by party colleagues during a Liberal group meeting. When Frederiksen discovered what had happened, he filed his own police report, believing his office had been broken into.

The next morning, February 8, new damning revelations emerged. B.T. revealed that the municipality had systematically overpaid a travel agency, Alletiders Rejser, by DKK 500.000 (RMB 560,000) for organizing the widely celebrated pensioner holidays to southern Europe. The excess money had then been funneled back to Farum BK, disguised as a sponsorship. The pattern of illicit municipal funds propping up Brixtofte’s pet project was now undeniable.

By February 9, the illusion of invincibility had evaporated. Police launched coordinated raids on city hall as well as several private residences, including those of Brixtofte and Municipal Director, Leif Frimand Jensen. Computers and mountains of files were seized as evidence. Faced with a full-blown crisis, Brixtofte reversed course. He returned to city hall, abandoning his leave and attempted to reassert control. But the kingdom was falling apart, and the king was defending a throne that was collapsing underneath him.

The wine, the sponsorships, the real estate grifts, these were only the surface. In the days that followed, a deeper structural rot was uncovered. Farum’s clever finances had been built on sand. The tax loopholes that once funded the city’s wonders had been closed years earlier and the municipality had no more assets to sell. The city was running massive deficits. To keep the illusion going Brixtofte had taken out two massive, unauthorized loans behind the back of the council, totaling DKK 450 million (RMB 504 mln.), burying the town under unsustainable debt. Municipal Director Leif Frimand Jensen had signed the loan agreements, despite knowing how the council had been kept in the dark. Farum was bankrupt.

On February 19, ten days after the first story broke, the national government struck. Lars Løkke Rasmussen, Brixtofte’s former admirer now Minister of the Interior in Anders Fogh Rasmussen’s newly elected government, put Farum under state administration and imposed a harsh austerity programme of huge tax hikes and sweeping service cuts, costing the average Farum household an extra DKK 1700 (RMB 19,000) per month. Brixtofte railed against this intervention, labelling it a "deeply unserious economic punitive action." He insisted his grand designs to redevelop the former military base would have saved Farum, flooding it with new taxpayers. He pointed fingers at the Fogh Rasmussen government, accusing them of a political vendetta and told how the press would often get access to relevant documents from the Ministry of the Interior before the Farum council got it.

His defiance was short-lived. On March 20, his council, overwhelmed by the scandal and the looming oversight, voted to suspend him. On May 13, the day before the suspension would take effect, he resigned as mayor. The next day, his own Liberal Party expelled him from their parliamentary group. By June 5th, he was purged from the local party branch in Farum itself.

The county oversight committee descended, fining 18 out of 19 councillors for negligence in their duties. Six pleaded guilty and paid the fines, 12 others went to court where they were all acquitted a few months later. Officials were ordered to repay misused public funds.

The scandal reached into the national government. Thor Pedersen, Brixtofte’s old ally who had once praised Farum as a "model municipality" was now Finance Minister and his name appeared as the scandal unfolded. During his time as CEO, Jydsk Rengøring, had received a lucrative, no-bid contract for municipal assisted living facilities in 1999, jumping an existing contract from 24 to 96 units, coinciding precisely with a substantial 450,000 DKK (RMB 504,000) sponsorship deal with Farum BK. The police questioned the Finance Minister but no charges were filed. Pedersen steadfastly denied any wrongdoing, eventually weathering the storm.

Brixtofte, now a pariah, scrambled to revive his political career. Parliament stripped him of his immunity from prosecution later in 2003. He briefly joined the Centre Democrats who had lost representation in parliament and were desperate for influence but even they would not let him run under their name in the 2005 general election due to the ongoing legal proceedings against him. Undeterred, he founded his own Social-Liberal Party which was quickly renamed the Welfare Party, following legal complaints from the Liberal Party. Brixtofte's Welfare Party managed a pyrrhic victory, winning back a single council seat for Brixtofte in the newly merged Furesø municipality later that year.

Looking for new revenue streams, Brixtofte turned to business in 2003. Together with the infamous slumlord and horse trader Låsby-Svendsen, he launched a Turkish real estate venture selling vacation homes to Danes in Antalya. It failed by 2008 as a result of the financial crisis.

The law, however, was relentless. His criminal case was split in two: the Sponsor Case and the Main Case. In 2006, he was convicted of gross misconduct for deliberately overpaying construction giant Skanska by 9 million DKK (RMB 10 mln.)for building Farum Arena, with the understanding the excess would be given as sponsorship to Farum BK's handball division Ajax Farum. He was sentenced to two years in prison. His appeal failed in 2007.

It was during the years of legal proceedings that his marriage for more than 20 years ended.

In 2008 he was found guilty of gross misconduct and abuse of public office in the Main Case, adding an additional two years to his sentence in addition to an order to pay 7 million DKK (RMB 7.8 mln.) in damages and legal fees. His former right-hand man, Leif Frimand Jensen, was convicted as well, receiving a suspended two-year sentence.

Later that same year, the Supreme Court upheld the Sponsor Case conviction. Brixtofte now had a final conviction to his name and the Queen stripped him of his knighthood. Lars Løkke Rasmussen, once his disciple, now as Minister of the Interior, formally barred him from his council seat. Peter Brixtofte began serving his sentence in an open prison.

His final act of defiance came in 2009. As his last appeal in the Main Case was rejected, he appeared on television, calling the presiding judge "an extreme nationalist" and accused him of pursuing a political vendetta against him. The performance earned him another conviction, this time for defamation, and a fine of DKK 10,000 (RMB 11,200).

He was released on parole in 2011. The friends and sycophants he partied with as mayor had abandoned him a long time ago. The kingdom was gone.

Legacy

Though infamous for his taste in expensive wine, few grasped the full extent of Peter Brixtofte’s alcoholism. After his political downfall in 2002, he cycled in and out of rehab, repeatedly failing to stay sober. From time to time gossip magazines would bring funny stories about his drinking. They wrote about the funny drunk, not about how he was hospitalized multiple times with alcohol poisoning or how his drinking drove a wedge between him and his three daughters, who often cut off contact for weeks or months as they could not bear being around him when he spiraled.

On November 8 2016 a police car and two ambulances pulled up in front of a Farum housing estate. Peter Brixtofte’s daughters had found him dead in his apartment, lying on the sofa. He had died alone, aged 66, several days before. The medical examiner ruled his death to be alcohol-related, a conclusion his daughter Maria later agreed to. She had not spoken to him for three weeks at the time of his death.

Following his downfall, parliament launched an official inquiry in 2003. Nearly nine years later, the Farum Commission released its findings: over 7,000 pages across sixteen volumes. Despite its staggering length, the report stopped short of recommending sweeping reforms. Its tangible outcomes were modest: changes to municipal legislation clarifying how councils could remove mayors mid-term, and improved training on minority rights and procedural safeguards for councillors. The story of Farum, of pride, hubris, and corruption, captured public imagination and has inspired several books and documentaries.

Lars Løkke Rasmussen’s 2004 local government reform forced smaller municipalities to merge. Farum, toxic and bankrupt, found itself without suitors. Neighboring Værløse, unwilling to merge into "the red sea" of neighbouring Social Democrat councils had secured no other options and found itself forcibly wedded to Farum by Løkke Rasmussen’s decree, creating the Furesø Municipality. Citizens of Værløse protested and the local council spoke of expropriation and hired lawyers but it was to no avail. The merger went ahead.

To soften the blow to Værløse, legislation was passed, levying a special tax on residents living in the former Farum municipality until 2013. The new municipality received a 50 million DKK (RMB 56 mln.) annual bailout until 2021. Farum’s citizens ended up paying the price for Brixtofte’s vision. Today the Furesø municipality has recovered, not to the heights of the Brixtofte age but to stable mediocrity, having a tax rate slightly below and a service level slightly above national averages.

Farum BK rebranded as FC Nordsjælland in a bid to shed association with the Brixtofte age and to appeal to a broader regional base. Being one of Brixtofte's few enduring legacies, the club survived the financial blow of the mayor's downfall and continues to play in Denmark’s top tier, having qualified for the Champions League several times.

Most insidiously, Brixtofte’s harsh workfare policies, once controversial for exploiting the vulnerable, entered the political mainstream and became a cornerstone of Danish labour policy. Although he remained critical of the racist turn of Danish politics to the end, the workfare model he championed became a tool wielded by islamophobic politicians. Today, both Liberals and Social Democrats alike consider underpaid coerced labour for the unemployed to be commonsensical tough love for the undeserving and racialised poor.

The origins of the leaks that brought Brixtofte down remain murky. His autocratic leadership style and ruthless political maneuvering earned him many enemies. Speculation persists that elements within the Liberal Party, recognizing Farum’s unsustainable finances as a ticking time bomb under the party’s "model municipality" narrative, orchestrated a controlled demolition. By turning the story of the systemic failure of an ideology into a story of a single man’s criminality, fixating on wine, property deals, and sponsorships, they avoided being tainted. For Prime Minister Anders Fogh Rasmussen, destroying his former rival would have felt like sweet revenge while also ridding him of a prominent internal critic of his national conservative turn.

Lars Løkke Rasmussen, who had been made prime minister by 2016, penned a warm eulogy for Brixtofte. He praised Brixtofte’s "drive and immense commitment," his "grand gestures" and "profound impatience to achieve results," framing the scandal not as corruption but as "irregularities" caused by this impatience. He expressed pain at having had to "put his foot down" as Interior Minister. He never had to answer for having embraced Brixtofte’s policies, including the infamous sale-and-leaseback schemes, as county mayor. His local government reforms dissolved the counties altogether, burying the financial wreckage in bureaucratic reorganization. Thor Pedersen retired with his reputation largely intact. The businessmen who profited from municipal contracts and facilitated the illicit sponsorships faced no consequences.

Shortly before his death, Brixtofte gave a final interview to B.T., the very tabloid that had first exposed him. He bore no grudge against the paper. He described the articles that brought him down not as an expose of criminal wrongdoing, but as sport, a fair game between him and the media where he had simply been outplayed by an opponent he underestimated. Once more he insisted on his innocence, calling the trials a “parody”.

In later interviews his daughter Maria would tell how he had been drunk while making most of the decisions that landed him in jail but during the interview he pointed to the official inquiry’s failure to prove decisively that alcohol had affected his judgement, claiming it vindicated him. He took pride in what he had built: the sports facilities, the elder care, the integration efforts. He had nothing but disdain for his successors and claimed that “nothing has happened in Farum” since his ouster. “I don’t regret shit,” he stated, recasting himself as a misunderstood jovial visionary, a far cry from the domineering narcissist described by those closest to him.

Peter Brixtofte refused to accept responsibility. He left behind a town in ruins and blamed everyone but himself. He didn’t regret shit. But he was full of it.

Stop threatening us with a good time