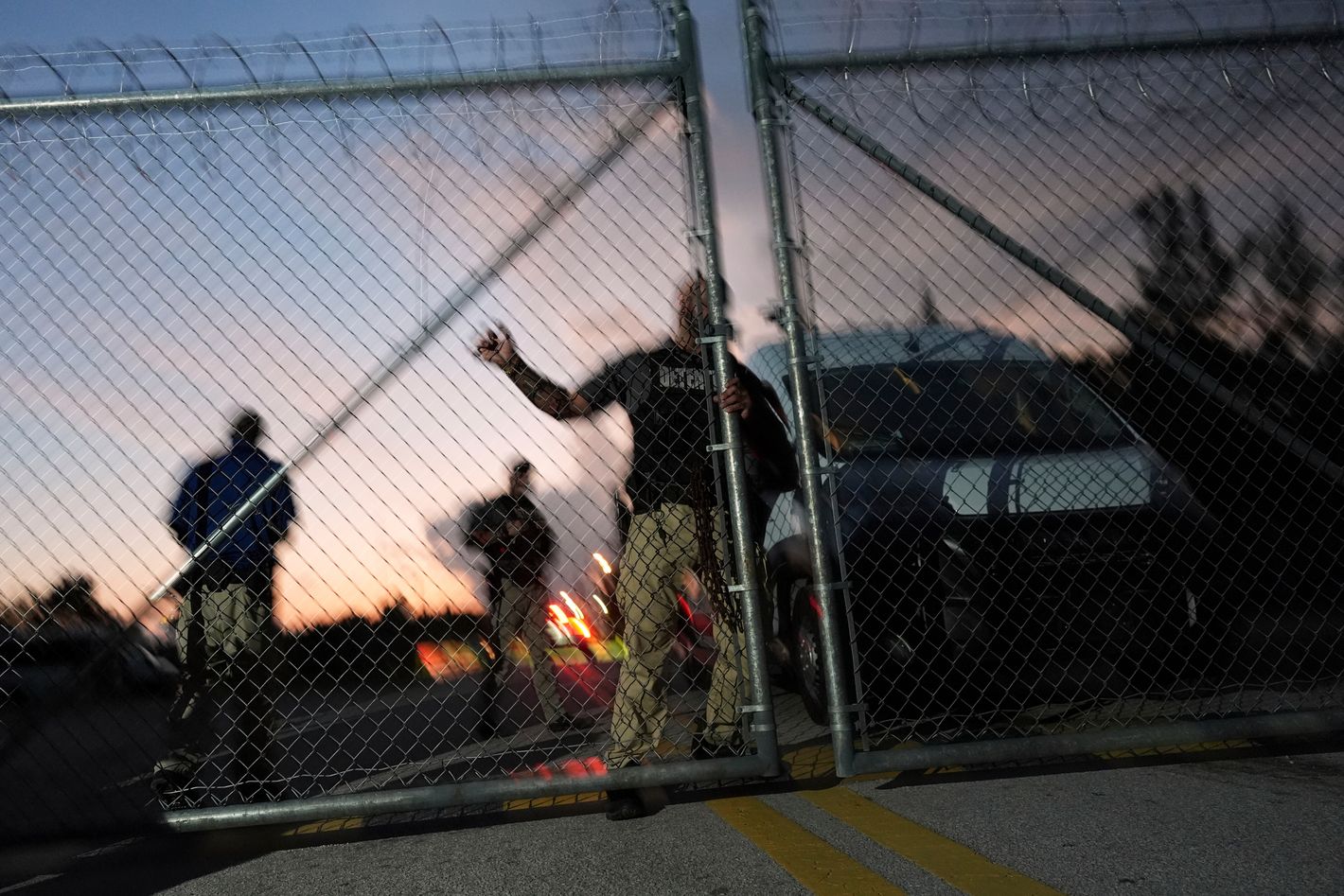

Photo: Rebecca Blackwell/AP Photo

Photo: Rebecca Blackwell/AP Photo

Five months into Donald Trump’s push to round up millions of immigrants, multiple U.S. citizens have been caught in the dragnet. In April, José Hermosillo, a 19-year-old from Albuquerque, spent ten days in detention before the government acknowledged he was a citizen and dismissed his deportation case. In Florida, highway-patrol cops enforcing the state’s new anti-immigration laws arrested a 20-year-old and tried to transfer him to ICE custody — even after his mother provided his birth certificate. A Puerto Rican U.S.-military veteran was detained during a workplace raid in Newark, New Jersey, in January. Some citizens have even been deported, all of them children deported along with their parents, including a 2-year-old American-born girl deported to Brazil, who is now effectively stateless.

If Immigration and Customs Enforcement arrests you for an immigration-related offense, and you tell the agency you are a citizen, it might not release you. Citizenship isn’t something that you wear on your body. Maybe you pull an ID, passport, or even a birth certificate, but agents frequently assume these are fake. In that case, you will be taken to a detention center, run by a private prison company. You can tell the guards there that you’re a citizen, but they’ll likely respond with some version of “tell it to the judge.” Your immigration-court appearance could be weeks, or even months, away. You will wait behind bars. There’s no right to counsel in immigration court — if you can’t afford a lawyer, you’ll have to represent yourself. When you finally see the inside of a courtroom, it could be what ICE calls a “mass removal” hearing with dozens of other defendants. You won’t have a chance to talk to a judge.

The U.S. citizens I’ve spoken to who have spent time in immigration jail describe fighting against a feeling of resignation — not just the temptation to give up on their legal case, but to give up on their belief that they are actually a citizen. Their sense of citizenship, with all its protections, dematerializes as soon as the government begins insisting they were in the country illegally. Peter Brown, a Philadelphia-born resident who spent three weeks in a local jail after ICE targeted him for deportation in 2019, told me he got whiplash: One day he was a free citizen, the next the government could keep him behind bars indefinitely. In his case, the agency’s error was simple — it had confused him with another Peter Brown, a Jamaican fugitive. In jail, he was staring down a deportation to a country he had only visited once, for a day trip on a cruise. “I really went into a state of panic,” Brown says. He repeated to his jailers that he was a citizen, and he offered to provide his birth certificate. He signed every document with, “Peter Sean Brown, United States Citizen.” It didn’t make a difference. Brown says that the last guard he saw before he was placed into the transport van ahead of deportation to Jamaica smirked at him and said, in a fake Jamaican accent, “Yeah, whatever, mon, everything’s gonna be all right.” After he was transferred to a detention center in Miami, an agent finally agreed to look at his birth certificate, and ICE released him.

Though immigration enforcement gets more attention under Trump, ICE, since its modern creation after 9/11, has mistakenly detained, and sometimes deported, thousands of U.S. citizens under presidents of both parties. What has changed under Trump is the government’s willingness to admit, and correct, its errors. In March, the administration rushed some 278 deportees to CECOT, the supermax hellhole of a prison in El Salvador, in violation of a court order. One of these deportations was, by the government’s own admission in court, a mistake: Kilmer Abrego Garcia should not have been deported. But when a judge demanded the administration return him, it shrugged: He was in El Salvador; it was too late now.

Trump has repeatedly floated the idea of sending citizens to El Salvador, and the government making this sort of “error” with a citizen in ICE custody would be one way to accomplish that before the courts intervene. It’s getting easier to see that day coming. In his pursuit of millions of deportations, Trump and his crew of true believers have argued it’s time to remove the safeguards and put the deportation machine into overdrive. “The right of ‘due process’ is to protect citizens from their government, not to protect foreign trespassers from removal,” White House adviser Stephen Miller posted online in May. “Due process guarantees the rights of a criminal defendant facing prosecution, not an illegal alien facing deportation.” (Last week, the government blamed “a confluence of administrative errors” for deporting another man in violation of a court order.) Miller’s reading of the Constitution wasn’t particularly impressive — the Fifth Amendment says that “no person” shall be deprived of due process, not “no citizen.” His logic, though, was even more suspect: What do the protections of citizenship mean without due process? If you have no chance to argue your case in court, how will you convince anyone you’re a citizen if you’re arrested by mistake?

When I read Miller’s post, and later heard Trump doubt that noncitizens should be afforded due process, there was one man I wanted to call: Davino Watson, who holds the known record for the longest amount of time a U.S. citizen has spent in ICE detention. Today, he lives in Brooklyn and works nights as a security guard in Manhattan. “What people are going through right now, and what happened to me, isn’t going to end anytime soon,” he tells me.

From 2008 to 2011, Watson spent 1,273 days — he counted them — in detention. It started in 2007, when Watson pleaded guilty to selling cocaine in a New York State court. This is how U.S. citizens often end up held by in ICE: Law-enforcement agencies around the country send names and biometric data to the Department of Homeland Security when they have suspects in custody. If a name or fingerprint pings on a database, ICE might request a “detainer” and ask the authorities to hold the person until the feds can come pick them up. This system is prone to errors. Even though he was a citizen, Watson’s name drew a flag; he showed up in the Feds’ database as a “deportable alien.”

There’s no master list of U.S. citizens, no reliable dataset immigration agents can refer to when they want to determine who is a citizen and who isn’t. Citizenship, as it exists on paper, is a conglomeration of documents, of birth certificates, Social Security cards, and naturalization papers. And it’s not simple. Even if you were born in the U.S., clerical errors can get you on record as a noncitizen. It’s even more difficult to prove citizenship for immigrants, like Watson, who was born in Jamaica. He immigrated, with a visa, to New York when he was 13 to live as a legal permanent resident with his father, also a legal permanent resident. A few years later, before Watson’s 18th birthday, his father became a naturalized citizen, which meant that, legally, Watson became a citizen as well.

Photo: Courtesy of the subject

Photo: Courtesy of the subject

While serving a short sentence for his cocaine charge, Watson learned that, after he finished his prison time, he’d be transferred to ICE custody and deported.From that moment, he maintained vehemently, and correctly, that was a citizen. In his first interview with agents, Watson explained his father was a citizen and he gave them his father’s phone number. In their records, the agents wrote a note to call him and “verify status.” His father could have easily provided his naturalization documents. But the agents never got in touch with him.

They did, however, look up his name, and Watson’s stepmother, in a database. This is where ICE made the mistake that would keep Watson behind bars for over three years: His father’s name was Hopeton Ulando Watson, and his stepmother was Clare Watson; both lived in New York. When searching, however, agents found a different couple: Hopeton Livingston Watson and Calrie Watson, two Jamaican citizens who lived in Connecticut. ICE decided these were Davino’s parents — even though their names were different, they lived in a different state, and Hopeton’s file listed no son named Davino. It didn’t matter. ICE opened deportation proceedings.

In an upstate detention center, Watson struggled to fight his case. “Once you go into a place like that, and you don’t have a good family backing you, or you don’t have an attorney, you’re screwed,” he says. “Because you’re gonna be ignored; because their job is to get you out of there as fast as possible.” With no right to counsel, Watson — who, at that time, didn’t have a GED — represented himself. He made do with the tiny law library in the detention center. In a series of handwritten letters, he appealed to the Board of Immigration Appeals. He spent most days locked up for 23 hours. “I’m still suffering from that stuff,” he says. He had panic attacks. He didn’t sleep. “But I told myself I had two options: give up or fight.”

Watson was able to get in touch with his father to get his naturalization papers, which he sent to the BIA. But there was little his family could do to support him, especially after he was moved far away from New York to a detention center in rural Alabama. Without a lawyer to push the courts to move, they had to wait for a legal process to play out at its own speed. It took years, but eventually the BIA, even with the naturalization papers in front of them, denied his request for a stay, concluding the government could deport him. The court’s argument was arcane: It maintained that Watson couldn’t prove his father had custody of him when he was naturalized.

In a rush, Watson filed an appeal in federal court just in time — that same night, ICE agents came to his cell and told him to pack up. He would have been deported if the district court hadn’t issued a stay. Once he was arguing in federal court, he was finally afforded a lawyer who pushed ICE to conduct its own internal review of his citizenship.

One day, guards came to his room without warning and said he was leaving. Watson made his way through the guts of the jail in a daze; a door opened and he was released into the Alabama sun. No one had told him why he was being released. He had no money and no phone; he was still wearing his prison jumpsuit. He had to cautiously approach strangers and ask if he could make a call, the start of a long journey home.

A court would eventually rule that Watson had been wrongfully imprisoned. But the statute of limitations to sue the government began the day he got locked in ICE detention; it had passed by the time he was released. “I never cared about the money — I just wanted justice,” Watson says. Since his time in jail, he has struggled with addiction and anxiety. Getting straight, he says, meant letting go: giving up on his wrongful imprisonment case and trying to move on. “If I didn’t, it would have destroyed me; I had to shake it off, had to let it go,” he says.

Unlike police, ICE agents almost never have to testify in court. In Watson’s case, the officers who made the mistakes that kept him in jail remained anonymous in all court documents; even the judges who incorrectly ruled that Watson should be deported remained anonymous, thanks to a Department of Justice arrangement that keeps immigration proceedings opaque. While the law is clear — ICE is not to arrest U.S. citizens — agents have such significant discretion, and such little accountability, that, in practice, the first opportunity a citizen will have to meaningfully contest their arrest is at their first court appearance. And that can take a while.

“When U.S. citizens sue for damages for wrongful imprisonment, and the government pays millions of dollars, no one gets fired; no ICE agents lose salaries,” says Jacqueline Stevens, a professor of political science at Northwestern University and director of the school’s Deportation Research Clinic. “It’s the U.S. taxpayers who are on the hook when ICE screws up.”

In 2017, Stevens began studying cases like Watson’s, combing court records for instances of ICE detainees being released after the government acknowledged they were citizens. She connected with dozens, including many who had been deported before the government could correct its error, and who got in touch with her from other countries. “This is happening all the time,” she says. In her study, she found that, on average, U.S. citizens detained by ICE spent 180 days behind bars. Deportation is always a real possibility. At a mass removal hearing she attended, Stevens remembers the judge declaring that all 50 defendants would be deported; as bailiffs cleared the room, a man stood up and shouted “I thought I’d have a chance to speak to a judge!”

Stevens and other legal experts offered the same prescription for the problem: more due process, not less. If he’d been afforded a lawyer from day one, it’s possible Watson wouldn’t have spent any time in jail.

Watson says that, looking back, he’s not confident that the damage long-term imprisonment did to his mind and body was worth it to remain in the country. “As lovely as America sounds, it’s not everything. It’s okay to start back over and live your life, because sometimes you’re gonna sit there for a long time if you’re fighting,” he says. His advice to other citizens in ICE detention is to remain open to giving up, if deportation means getting out of jail. “But if you feel like you were wronged and you feel you have a strong case — you can do it. Fight. Just know it’s gonna be hard.”

Related

A Mother Took Her Sons to an ICE Check-in. She Never Saw Them Again.

From Intelligencer - Daily News, Politics, Business, and Tech via this RSS feed

Photo-Illustration: Intelligencer; Photos: Getty Images

Photo-Illustration: Intelligencer; Photos: Getty Images Photo-Illustration: YouTube/ Josh Gottheimer for Congress

Photo-Illustration: YouTube/ Josh Gottheimer for Congress Photo: Roy Rochlin/Getty Images for (BAM) Brooklyn

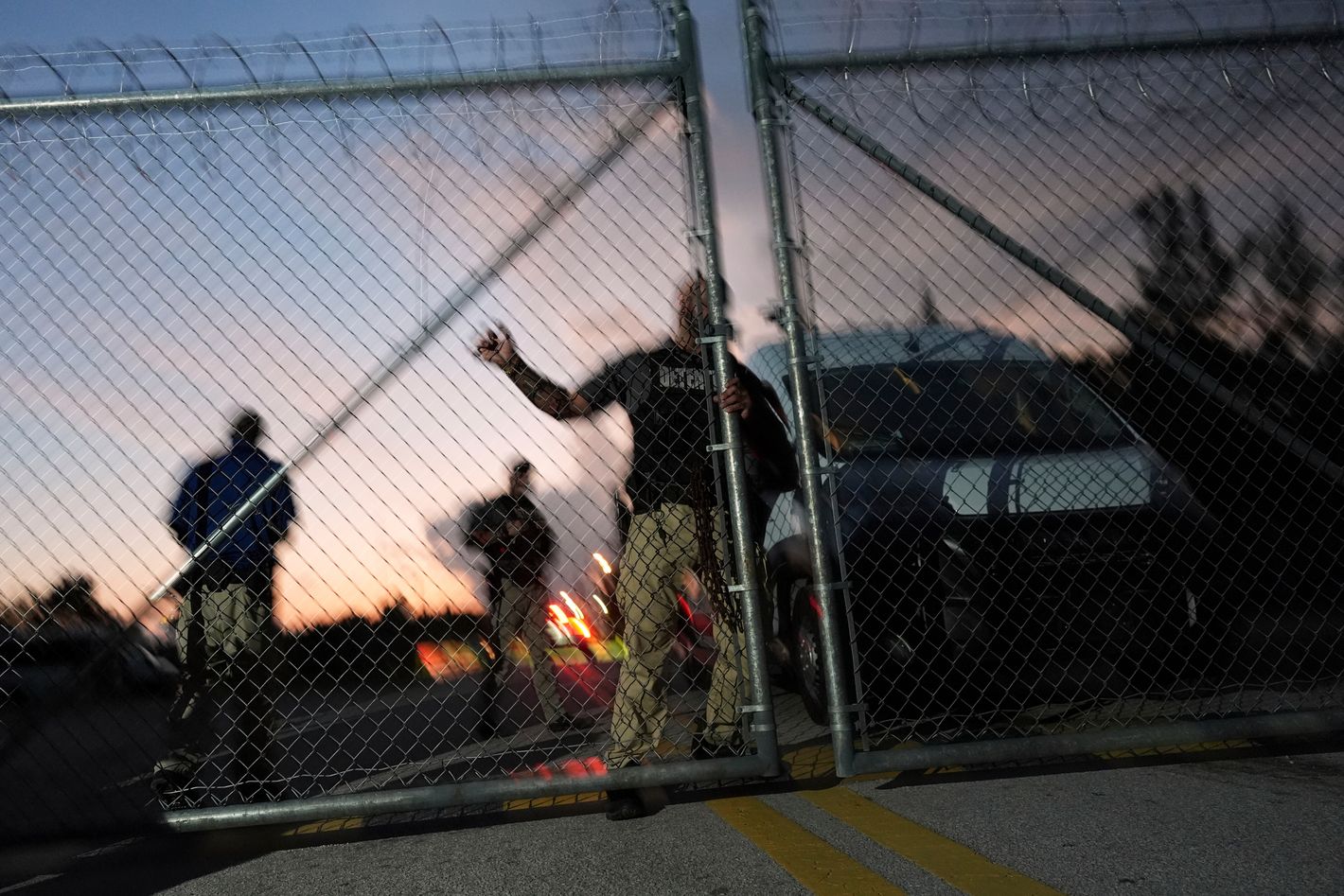

Photo: Roy Rochlin/Getty Images for (BAM) Brooklyn Photo: Rebecca Blackwell/AP Photo

Photo: Rebecca Blackwell/AP Photo Photo: Courtesy of the subject

Photo: Courtesy of the subject