Walking through Providence, Rhode Island, it’s hard to miss the flyers posted on storefronts, bulletin boards, and lamp posts rallying passersby with a defiant call to action: Let’s Fight Trump’s Fascism! Defend Our Communities! Build a Better World! Come to the Providence General Assembly.

For months, popular assemblies such as these — in Providence, Detroit, and Richmond, Virginia — have been diligently laying the groundwork for resisting Trump’s agenda and building self-governance. In Providence, organizers with the General Assembly tabled at last weekend’s No Kings demonstration, which drew thousands. Some members help operate a hotline for reporting Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) sightings, a key part of deportation defense efforts that helps alert communities to raids, and makes large-scale, coordinated responses — like those in Los Angeles — more likely to materialize.

But what is a popular assembly, exactly? In Providence, assemblies have been held every other Saturday in a downtown Methodist church since November of last year. These gatherings offer a space for anti-fascist and progressive forces to coordinate, strategize, and make decisions together to build power that can be leveraged against the U.S. government. “We need regularly scheduled radically-democratic meetings to organize, coordinate, mobilize in active defense of our friends, neighbors, and loved ones,” the Providence General Assembly (PGA) writes in its mission statement, “and to fight to create the type of communities and world we want through our collective actions.”

The assemblies are open to all. At a Providence assembly attended by Truthout in March, the atmosphere was warm and welcoming for newcomers. Attendees were greeted at the door by PGA organizers and directed to a table stocked with name tags, free masks, snacks, printed meeting agendas, and informational pamphlets. Community agreements — posted on the wall in both English and Spanish — encouraged participants to stay curious, open, and respectful, and to give and receive feedback with honesty and compassion.

To open the meeting, two facilitators welcomed the semicircle of about 75 people, guiding them through a preset agenda crafted by the Providence General Assembly’s coordinating committee, a group open to anyone who’s attended at least one gathering. Voices from across the room spoke up during the announcement period and open forum, with attendees raising hands to share updates, concerns, or reflections. Five working groups — Mutual Aid, Community Defense, Unhoused Solidarity, Class Struggle, and Anti-Imperialism — briefly summarized their recent efforts in report-backs. Mutual Aid was organizing a mental health free clinic, cooked free meals for the public every weekend, and was involved in starting a community garden at a local school. Anti-Imperialism was collaborating with Jewish Voice for Peace Rhode Island’s campaign to divest from Israel bonds. Community Defense publicized the ICE Watch Defense Line and an upcoming demonstration at ICE headquarters.

The meeting culminated with a proposal to organize a family-friendly May Day demonstration. Several members had brought forward this proposal through the PGA’s formal decision-making process, which asks sponsors to submit proposals 24 hours in advance of the assembly and introduce them formally during the meeting, where it is then debated and discussed, and finally voted on. Proposals must win the support of at least two-thirds of assembly attendees to be adopted/passed.

A lively 20-minute discussion of the May Day demonstration followed, with time set aside for clarifying questions, suggested amendments, and objections. Some attendees weighed the benefits and drawbacks of securing a city permit, while others questioned the strategy of protesting in front of vacant buildings. One participant voiced concern about whether there was enough time to pull the event together. “We’ll try our darndest!” a sponsor responded with a grin. Another sponsor invoked the memory of Providence’s 2006 May Day demonstration, which had drawn hundreds of immigrant workers into the streets. They noted that the PGA was the most broad-based, nonsectarian organizing space seen in Providence in years. In the end, with no major objections and energy high in the room, the proposal passed easily — clearing the required two-thirds majority and sparking a round of applause and celebratory cheers.

A National Movement

Similar people’s assemblies that have taken root in cities like Detroit, Michigan, and Richmond, Virginia, signal the rise of a national movement for self-governance in response to growing authoritarianism in the United States.

Hundreds joined the first People’s Assembly in Detroit on January 26, rallying around one clear and urgent goal. “We have a solid stance against ICE, that is the bottom line,” said Ame, a Detroit-based organizer who helped launch the initiative and withheld their last name because of privacy concerns. To put this stance into action, the assembly formed several working groups to support immigrant Detroiters in different ways.

The mutual aid group operates a hotline connecting residents with legal and material support, and offers weekly immigration office hours to provide legal education and assist with paperwork.

The political education group organizes events and actions, including know your rights training and public demonstrations.

Meanwhile, a third working group called Migra Watch patrols local neighborhoods and attends court hearings, monitoring ICE activity on the ground. When they witness an arrest, they try to collect the individuals’ contact information in order to alert their families and help secure legal support.

“We want to make sure that ICE and all the agencies working with them know they’re not welcome here,” Ame said. “We’re not going to allow people to just be kidnapped and taken away, to have our communities ripped apart and destroyed.”

Most recently, the People’s Assembly in Detroit has begun training local businesses on how to respond to ICE raids. On June 11, assembly organizers rallied outside of the McNamara Federal Building in downtown Detroit after several asylum seekers were detained following their court hearings due to expanded “expedited removal” policies. On June 8, assembly organizers attended a Detroit Public School’s Community District Board meeting to demand that the board take a stand in support of Maykol, a student who was detained by ICE. “Maykol was 3.5 credits away from graduating,” said Ame. “The board made the statement, but he still got detained so we’ve been fundraising, noticing that people who have lawyers are less likely to get deported.”

Across the board, the assemblies are committed to building people’s power beyond the confines of the electoral system. A spokesperson for the Richmond People’s Assembly, who goes by the moniker Ezra, explained that while voting and electoral strategies can sometimes lead to short-term improvements, they ultimately disempower communities by transferring power to officials who rarely bear the consequences of the policies they impose. The assembly hopes to return that decision-making power to the people who have to live with the outcomes of those decisions.

To pursue these goals, Richmond held its first citywide assembly on January 18, drawing a crowd of more than 500 people. During that initial gathering, a group of organizers introduced a proposal to create neighborhood-based assemblies. The proposal passed, and nine neighborhood assemblies have formed across the city in the months since. Since then, they’ve organized community CPR classes, “swap parties” with free clothing and other goods, community discussions with potlucks, block parties, and more.

“We wanted people to be able to address hyperlocal problems,” Ezra explained when asked about the neighborhood-based strategy. “We felt like we couldn’t start at the citywide level without it just becoming an organization of organizers.” The goal is to engage residents who aren’t already politically active — to avoid replicating the racial, class, and age conformity that can sometimes characterize grassroots organizing efforts. One neighborhood assembly is loosely connected to a squatted community garden that’s drawn a diverse crowd — something Ezra sees as a meaningful step toward building broader solidarity. Still, they admitted that the strategy is a work in progress for the relatively short-lived experiment. “[The assemblies are] definitely still mostly folks who are already in organizing circles,” they said, “and that’s something we’re actively trying to push past.”

Organizers with Detroit’s assembly also promoted the strategy of supporting neighborhood assemblies in a piece they wrote for Left Voice, highlighting the need to support workers and community members at sites where ICE raids happen, like schools and hospitals (as opposed to solely forming “roaming squads” that may be disconnected from impacted communities).

In Richmond, organizing efforts also extend beyond the neighborhood level by hosting quarterly city-wide gatherings, which offer workshops, informal socializing, and shared meals in addition to an assembly. “That flow of energy from a meeting setting into these more open forum workshops was really appealing to people,” Ezra reflected. “It’s what helped folks stay engaged through what was nearly a 10-hour day.”

At the heart of these gatherings is the assembly component, which links Richmond’s nine neighborhood assemblies through a spokescouncil. Each neighborhood sends two spokespeople — not to make decisions on behalf of their group, but to communicate important information and report their group’s interests to the wider assembly. This structure is designed to keep power decentralized by preventing a person or small group from wielding a disproportionate amount of influence over others.

This spokescouncil model, Ezra explained, draws inspiration from international examples of direct democracy — most notably Rojava, a multiethnic, feminist movement involving more than 4 million people in North and East Syria. In Rojava, most neighborhoods host at least one “commune,” a form of popular assembly that functions as both a decision-making space and a hub for coordination. These communes manage society’s core needs through dedicated committees for self-defense, food, water, education, electricity, heating oil, health, and garbage collection. Each commune is led by two co-presidents, one male and one female, who convene in regional assemblies. Similarly, every committee is represented by co-spokespeople who meet with their counterparts across the region, forming a federated structure of grassroots governance.

In Syria, years of grassroots organizing — door-knocking and deep conversations with neighbors about their shared struggles — helped build up social acceptance for revolutionary ideologies among the Kurdish population. So when many of Assad’s forces withdrew from North and East Syria in 2012, amid the chaos of the Syrian Civil War, communities were ready to self-organize. Masses of people stepped in to fill the power vacuum to build a new, participatory form of governance.

Without access to formal municipal power as in Rojava, assemblies in Richmond have conducted visualizations and thought experiments about what large-scale self-governance could look like. At the citywide gathering in April, the assembly used a recent water crisis in the city as a springboard for discussing current power structures in Richmond, and to imagine what it would take to build infrastructure capable of managing water for hundreds of thousands of people.

Turning such ambitious visions into reality requires scaling up our movements. For Ezra, the movement’s ability to grow and generalize hinges on recognizing how organizational structures (or the lack of them) influence the quality and scope of our relationships. “People often say that this is relational work, and that is true, but it is only true so far as your relationships are in community, are in dialogue with structure,” they said. “There is a dialectic between relationship and structure that allows for organization. When we lean too far into either end, we will pigeonhole ourselves into either subcultural party scenes, or into a very rigid form of politics that never steps into the real world.”

At a late-March assembly in Providence, participants similarly grappled with the dual challenge of building meaningful relationships while resisting the pull of subcultural insularity. A proposal to form a social committee for organizing and promoting nonpolitical events was ultimately voted down after a thoughtful and good-faith debate. While many assembly-goers agreed on the importance of building connections, they emphasized that relationships would develop organically within the working groups themselves and through shared struggle approached with sincerity, curiosity, and joy.

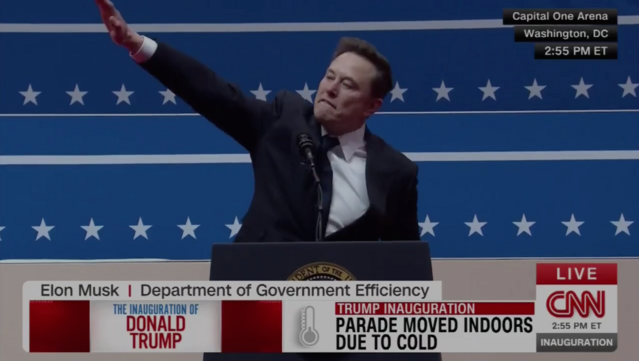

That spirit came to life a month later during the May Day demonstration, when a crowd gathered together to gleefully thwack effigies of President Donald Trump and a Tesla Cybertruck. It was a collective and cathartic act symbolizing a vision shared by all three assemblies: the dismantling of oppressive systems and the creation of liberatory structures in their place, of a world where people live without the constant fear of displacement, deportation, and state violence.