Over the past two decades, the VPN industry has grown spectacularly, with plenty of competition between providers.

Over the past two decades, the VPN industry has grown spectacularly, with plenty of competition between providers.

The days when a review of VPN logging policies was a novelty are long gone.

While new VPN services launch frequently, it’s rare to see one with a truly unique technical approach. That’s why VP.net warrants a closer look. Unlike most VPN providers, it doesn’t ask users for their trust; it relies on hardware-enforced privacy instead.

Trust

When you use a VPN, your internet traffic is encrypted between your device and the VPN’s server. This is great for protecting your data from snooping on public Wi-Fi and your internet provider. However, to route your traffic to its final destination on the internet, the VPN server must decrypt it first.

At this decryption point, it’s technically possible for the VPN provider to access information about your online activity. This is common knowledge and requires that you trust your VPN. It’s also why using shady free VPN apps from unknown companies should be avoided; the user may end up being the product.

For a successful VPN service to thrive, trust, security, and privacy are paramount. Reputable VPN companies build their entire business model on trust, knowing that a breach would be catastrophic for their reputation.

But what if trust was taken out of the equation entirely? This is what VP.net promises to do, at least up to a point.

VP.net

Like most VPNs, VP.net hides your real IP-address, replacing it with the address of the server you connect to. This connection is encrypted using the popular open-source WireGuard protocol and can’t be spied on by outsiders.

What makes VP.net stand out from many regular VPNs is its special use of a technology called Intel Software Guard Extensions (SGX). SGX enclaves are private areas of memory that essentially act as a secure black box and not even the operators of the service can see what’s happening inside.

VP.net

The system within the SGX enclave is reportedly built to map user identities to temporary, anonymous tokens. This means the part of the system which knows that “User X is connected” is structurally walled off from the part that knows “someone is accessing website Y.” The design goal is that no one, not even the VPN company, can link “User X” to “Website Y.”

The use of SGX as a verifiable, hardware-enforced separation of user identity and web traffic, is a new concept for a VPN.

‘Verified Privacy’

VP.net essentially promises “verified privacy” with this technical setup. If everything works as described, it’s not technically possible for the owners of the server, typically the VPN provider, to log who is doing what and when.

The new VPN service is operated by the American company VP.NET LLC, which in turn is owned by TCP IP Inc, which holds the intellectual property rights. That includes pending patents, including one of ‘hardware-based anonymization of network addresses.”

The idea to use SGX as a privacy shield comes from Andrew Lee, the chief privacy architect at VP.net. As the founder of Private Internet Access, which he sold to Kape a few years ago, Lee has a long history in the VPN space. However, he believes this new concept is a breakthrough.

“Our zero trust solution does not require you to trust us – and that’s how it should be. Your privacy should be up to your choice – not up to some random VPN provider in some random foreign country,” Lee says.

VP.net says it cannot link traffic data to users, even if it wanted to. If a court order requested such data, the company would first scrutinize its legality but, after that, the only data it has access to are unlinked details, such as payment info and email addresses, provided by the user.

The new VPN company is led by CEO Matt Kim. The company also lists the contentious Bitcoin veterans Roger Ver and Mark Karpelès in their team, who both have had their legal issues in the past.

Novel, Secure, but Not Infallible

VP.net’s source code is open to the public. To address the challenge of showing that this open-source code is the same as the code running on their servers, VP.net relies on a key SGX feature called ‘remote attestation’.

In essence, this mechanism allows the user’s client to receive cryptographic proof from the server’s hardware, verifying that it is a genuine SGX ‘safe’ and is running the exact, untampered code that was publicly available. This shifts the trust from the company’s promise to a verifiable, hardware-backed process.

The trust through technology aspect is certainly intriguing, but no technology is infallible. The code needs to be functional and secure, as a software flaw could lead to potential security issues.

Another potential problem lies on the hardware side. Intel SGX itself is a physical product that is part of the CPU, which in turn relies on firmware. Like any piece of hardware, vulnerabilities have been discovered in SGX in the past.

VP.net is aware of this and says it actively monitors the security of its software and infrastructure, while keeping systems fully up-to-date.

Of course, the true test will be speed and transparency when responding to the next major SGX vulnerability, a scenario for which all users should be prepared.

It’s safe to say that one should never have 100% trust in any VPN solution. In this case, VP.net promises to offer an extra layer of privacy but, in the end, even the most secure systems can be breached.

That said, it is interesting to see a novel approach to the ‘no logging’ discussions. Whether this novelty will scale and be embraced more broadly remains to be seen.

From: TF, for the latest news on copyright battles, piracy and more.

From TorrentFreak via this RSS feed

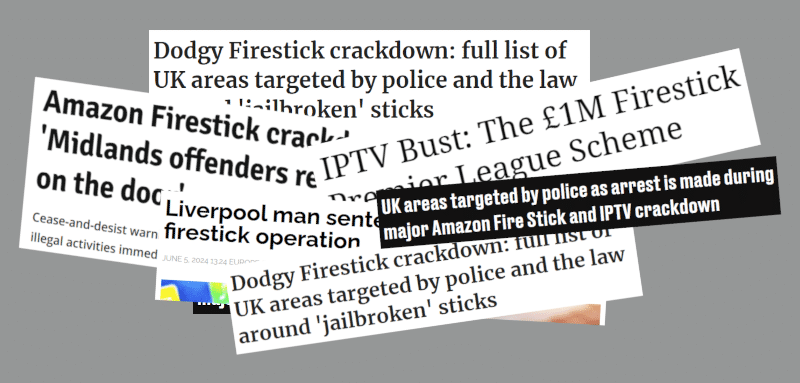

With almost no exceptions, people criminally prosecuted in the UK for serious pirate IPTV offenses say that it’s an absolutely horrendous experience.

With almost no exceptions, people criminally prosecuted in the UK for serious pirate IPTV offenses say that it’s an absolutely horrendous experience.

Always sold at highly competitive prices that almost anyone can afford, Amazon’s Fire TV Stick has enjoyed more than a decade of success, driving millions to the company’s video and online retail platforms.

Always sold at highly competitive prices that almost anyone can afford, Amazon’s Fire TV Stick has enjoyed more than a decade of success, driving millions to the company’s video and online retail platforms. When enduring popularity among pirates, on whom not a single marketing penny had ever been spent, was combined with a targeted campaign in the media that successfully reached

When enduring popularity among pirates, on whom not a single marketing penny had ever been spent, was combined with a targeted campaign in the media that successfully reached

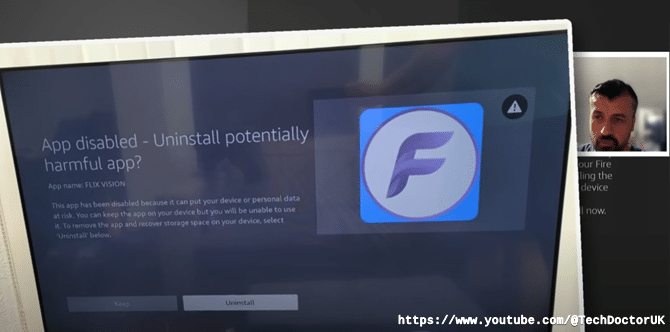

On one hand, Amazon’s interventions may have prevented greater harms being inflicted later down the line, and users should appreciate that. Yet by providing precious little detail on the nature of the threat, users won’t be able to learn from their mistakes or share knowledge on how these specific apps behaved and why they presented such risk.

On one hand, Amazon’s interventions may have prevented greater harms being inflicted later down the line, and users should appreciate that. Yet by providing precious little detail on the nature of the threat, users won’t be able to learn from their mistakes or share knowledge on how these specific apps behaved and why they presented such risk. After a decade of focusing efforts overseas, the push for pirate site blocking has landed back on American shores.

After a decade of focusing efforts overseas, the push for pirate site blocking has landed back on American shores.

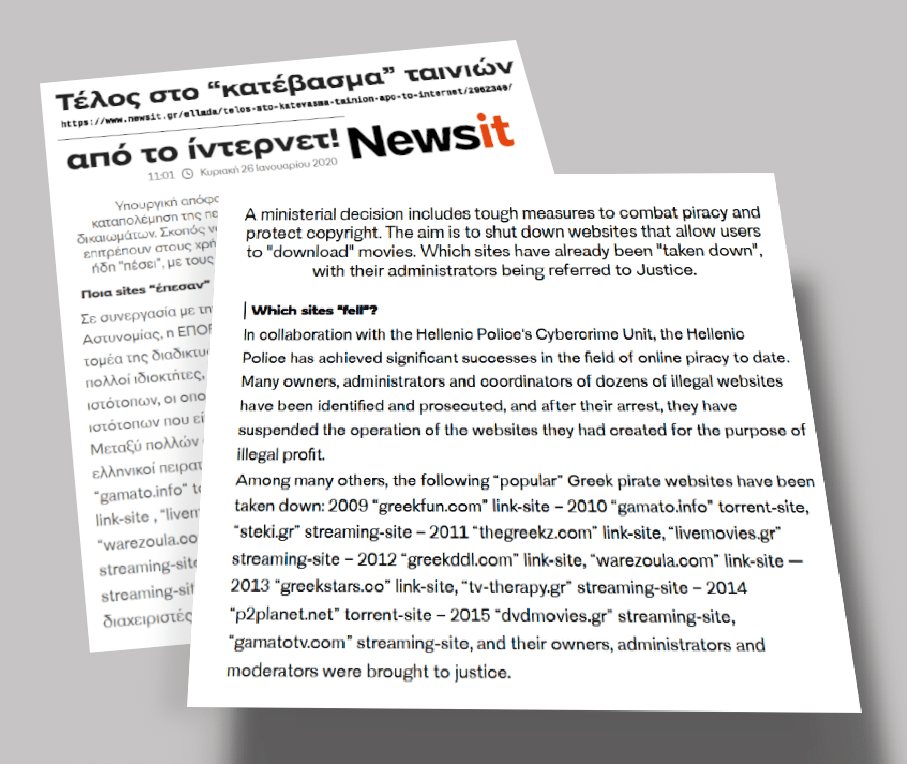

Online piracy is a global problem for copyright holders, but some threats are relatively localized.

Online piracy is a global problem for copyright holders, but some threats are relatively localized.

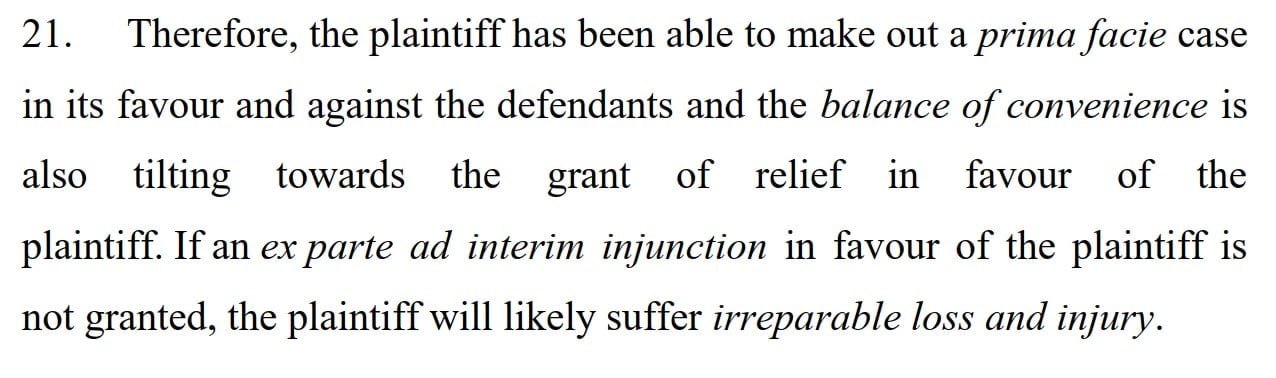

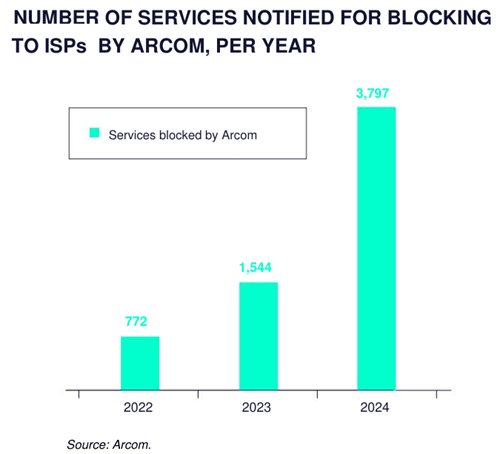

Selling pirate IPTV subscriptions has always been illegal and after the EU’s top court confirmed as much in 2017, consuming unlicensed content is illegal too. Nevertheless, these offenses are typically treated differently.

Selling pirate IPTV subscriptions has always been illegal and after the EU’s top court confirmed as much in 2017, consuming unlicensed content is illegal too. Nevertheless, these offenses are typically treated differently.

Over the past two years, rightsholders of all kinds have filed lawsuits against companies that develop AI models.

Over the past two years, rightsholders of all kinds have filed lawsuits against companies that develop AI models.

The High Court in Delhi, India, regularly issues site blocking orders, requiring Internet providers to block access to pirate sites.

The High Court in Delhi, India, regularly issues site blocking orders, requiring Internet providers to block access to pirate sites.

Hot on the heels of a live sports piracy

Hot on the heels of a live sports piracy

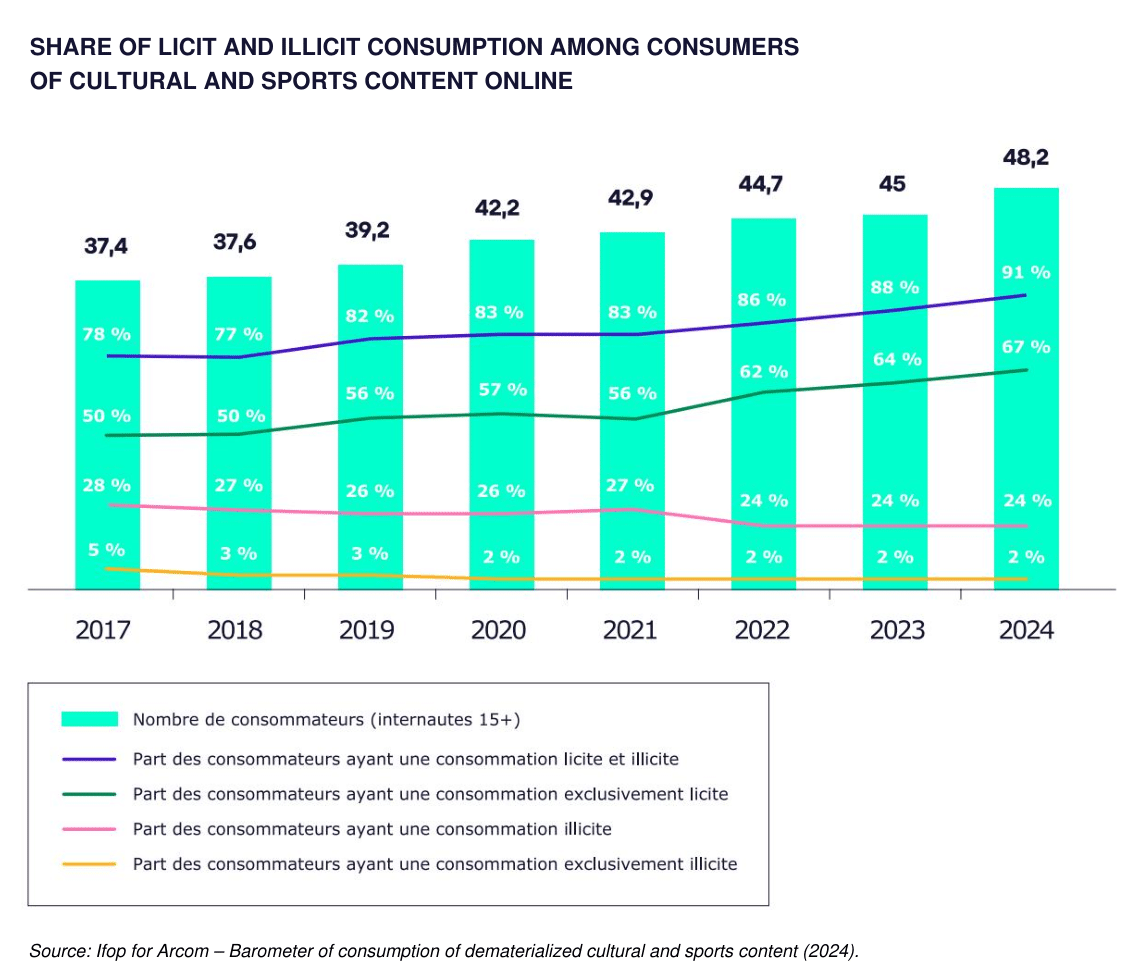

Processing increasing numbers of blocking requests was streamlined last year with the introduction of a new system at Arcom.

Processing increasing numbers of blocking requests was streamlined last year with the introduction of a new system at Arcom.

Sky’s war on TV piracy has raged for well over thirty years and despite the passing of time, the goal remains the same.

Sky’s war on TV piracy has raged for well over thirty years and despite the passing of time, the goal remains the same. Last year, Italy officially implemented the ‘

Last year, Italy officially implemented the ‘ The most obvious downward piracy trends have arrived in response to rightsholders addressing market demands.

The most obvious downward piracy trends have arrived in response to rightsholders addressing market demands.

In a complaint filed at a Nashville federal court two years ago, Universal Music, Sony Music, EMI and others, accused X Corp of

In a complaint filed at a Nashville federal court two years ago, Universal Music, Sony Music, EMI and others, accused X Corp of

In countries where site-blocking has been established for years, relatively small but always expanding measures happen mostly unannounced. It’s often too late to complain when the public are the last to know.

In countries where site-blocking has been established for years, relatively small but always expanding measures happen mostly unannounced. It’s often too late to complain when the public are the last to know.

In the late ’90s, with P2P file-sharing yet to really take off, music industry insiders had already toyed with the idea of a ‘celestial jukebox’ that could access all music in the world.

In the late ’90s, with P2P file-sharing yet to really take off, music industry insiders had already toyed with the idea of a ‘celestial jukebox’ that could access all music in the world.

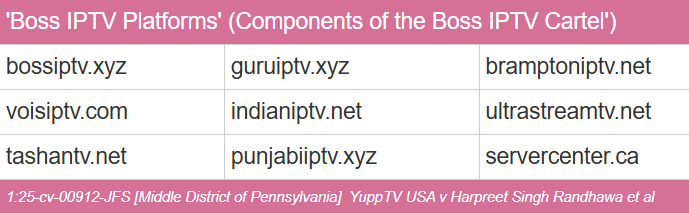

Incorporated in Georgia, YuppTV USA Inc. markets itself as one of the world’s largest internet-based TV and on-demand platforms for South Asian content. Most of the company’s subscribers are described as “non-resident individuals.”

Incorporated in Georgia, YuppTV USA Inc. markets itself as one of the world’s largest internet-based TV and on-demand platforms for South Asian content. Most of the company’s subscribers are described as “non-resident individuals.”

The basis for YuppTV’s claim against Infomir is far from clear. Even with an especially broad view of what type of conduct may amount to contributory infringement, nothing really stands out based on the information provided.

The basis for YuppTV’s claim against Infomir is far from clear. Even with an especially broad view of what type of conduct may amount to contributory infringement, nothing really stands out based on the information provided.

Pirate sites and services can be a real challenge for rightsholders to deal with. In India, however, recent court orders have proven to be quite effective.

Pirate sites and services can be a real challenge for rightsholders to deal with. In India, however, recent court orders have proven to be quite effective.

In 2023, sports rightsholders and their broadcasting partners had their collective patience tested to the limit.

In 2023, sports rightsholders and their broadcasting partners had their collective patience tested to the limit.

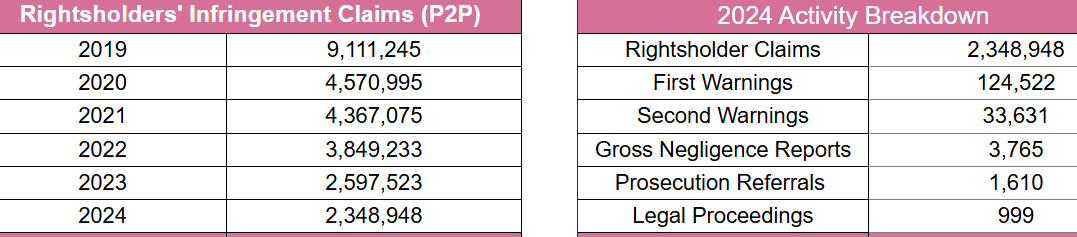

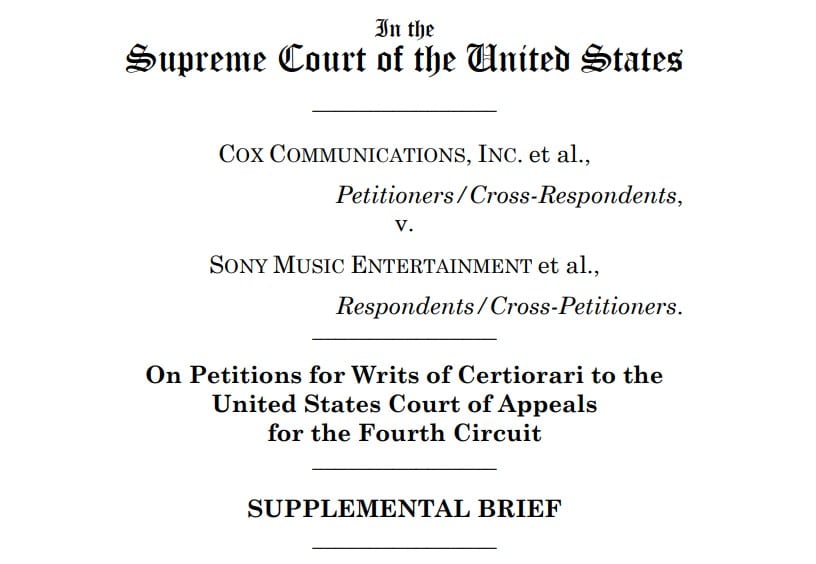

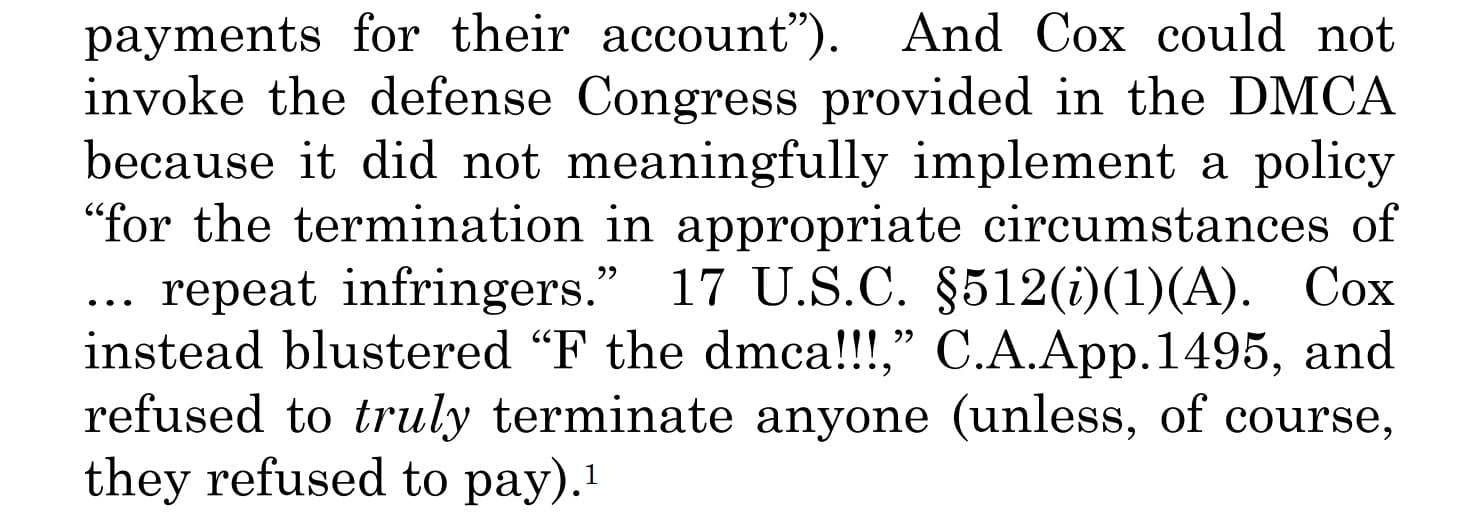

After a Virginia jury ordered internet provider Cox to pay $1 billion in damages for failing to take appropriate actions against pirating subscribers, shockwaves rippled through the ISP industry.

After a Virginia jury ordered internet provider Cox to pay $1 billion in damages for failing to take appropriate actions against pirating subscribers, shockwaves rippled through the ISP industry.

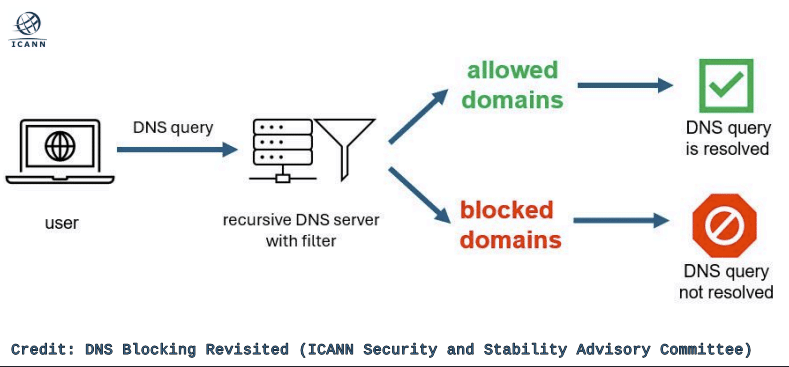

Traditional site-blocking measures that require local ISPs to block subscriber access to popular pirate sites, have been utilized by rightsholders in France for years. The aim is to deter piracy by making sites more difficult to find, but these measures are only partially effective.

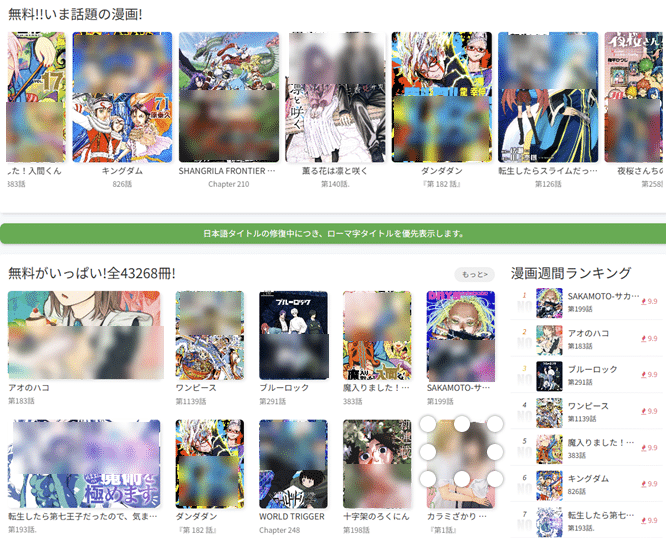

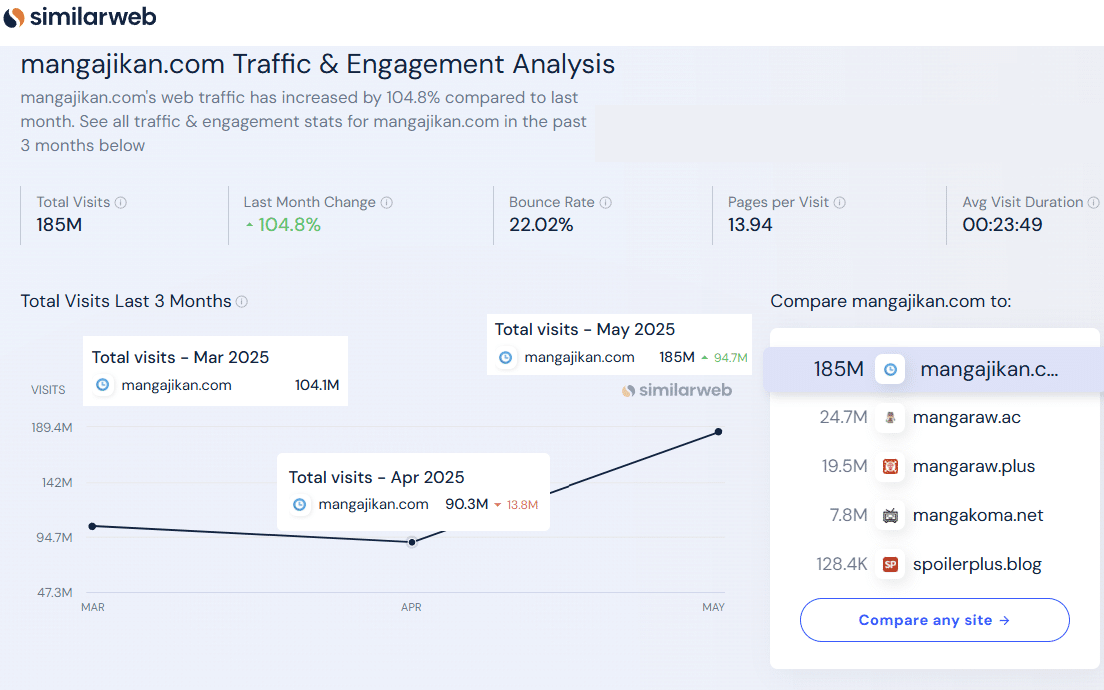

Traditional site-blocking measures that require local ISPs to block subscriber access to popular pirate sites, have been utilized by rightsholders in France for years. The aim is to deter piracy by making sites more difficult to find, but these measures are only partially effective. The extraordinary online popularity of Japanese manga comics shows no sign of retreat, with pirate site-based consumption at unprecedented levels fueled by

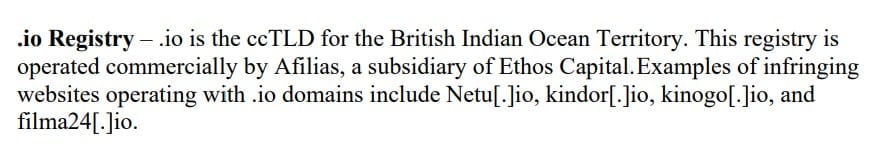

The extraordinary online popularity of Japanese manga comics shows no sign of retreat, with pirate site-based consumption at unprecedented levels fueled by  Shueisha’s subpoena target is Cloudflare and having already served DMCA takedown notices as required, Shueisha should receive data for around two dozen pirate domains.

Shueisha’s subpoena target is Cloudflare and having already served DMCA takedown notices as required, Shueisha should receive data for around two dozen pirate domains.

While that domain also makes an appearance in the DMCA subpoena application, Semrush data reveals that around 20% of outbound traffic went directly to a more suspicious looking domain. For obvious reasons we’re not naming it here.

While that domain also makes an appearance in the DMCA subpoena application, Semrush data reveals that around 20% of outbound traffic went directly to a more suspicious looking domain. For obvious reasons we’re not naming it here. Earlier this month, dozens of rightsholders and copyright groups urged the European Commission to pave the way for more robust measures to tackle live-streaming piracy.

Earlier this month, dozens of rightsholders and copyright groups urged the European Commission to pave the way for more robust measures to tackle live-streaming piracy.

In countries where protection is granted automatically, it’s possible for ordinary people to become copyright owners in a matter of minutes.

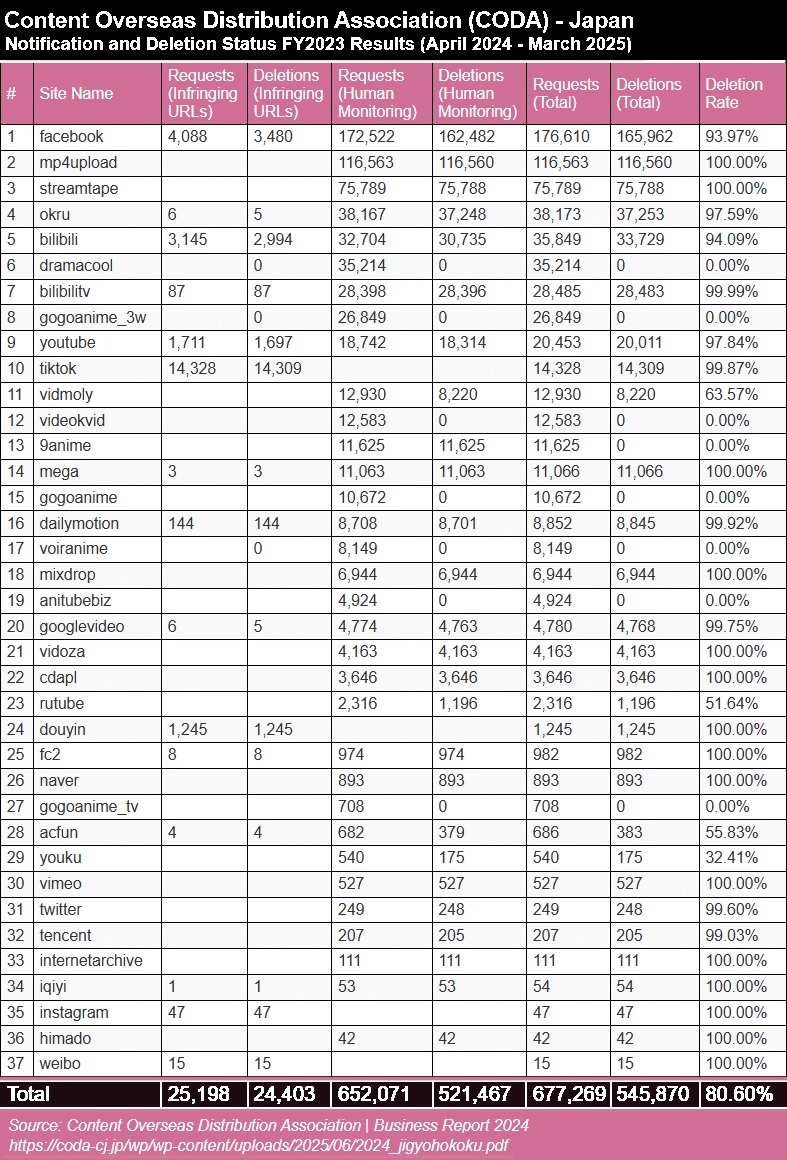

In countries where protection is granted automatically, it’s possible for ordinary people to become copyright owners in a matter of minutes. Japan-based anti-piracy group CODA represents the world’s leading manga publishers.

Japan-based anti-piracy group CODA represents the world’s leading manga publishers.

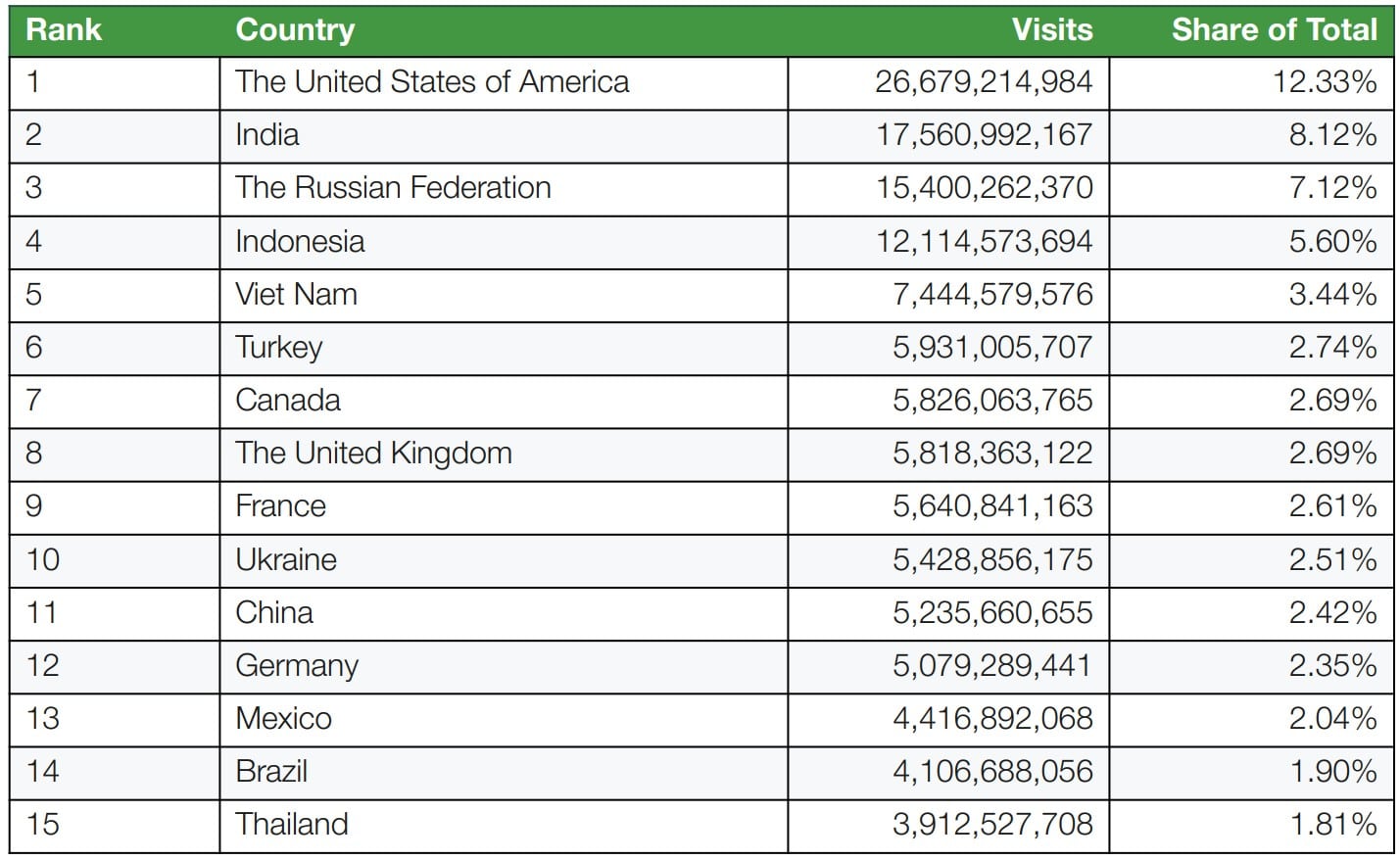

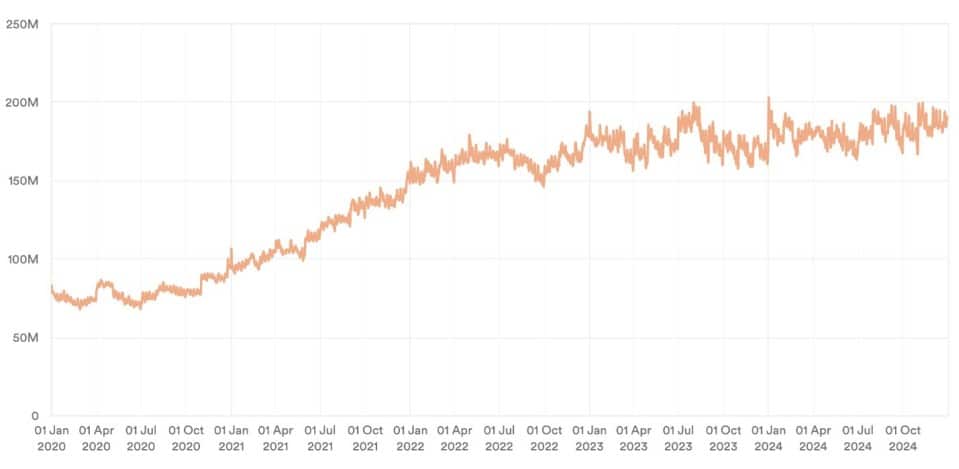

Despite the widespread availability of legal options, online piracy remains rampant. Every day, pirate sites are visited hundreds of millions of times.

Despite the widespread availability of legal options, online piracy remains rampant. Every day, pirate sites are visited hundreds of millions of times.

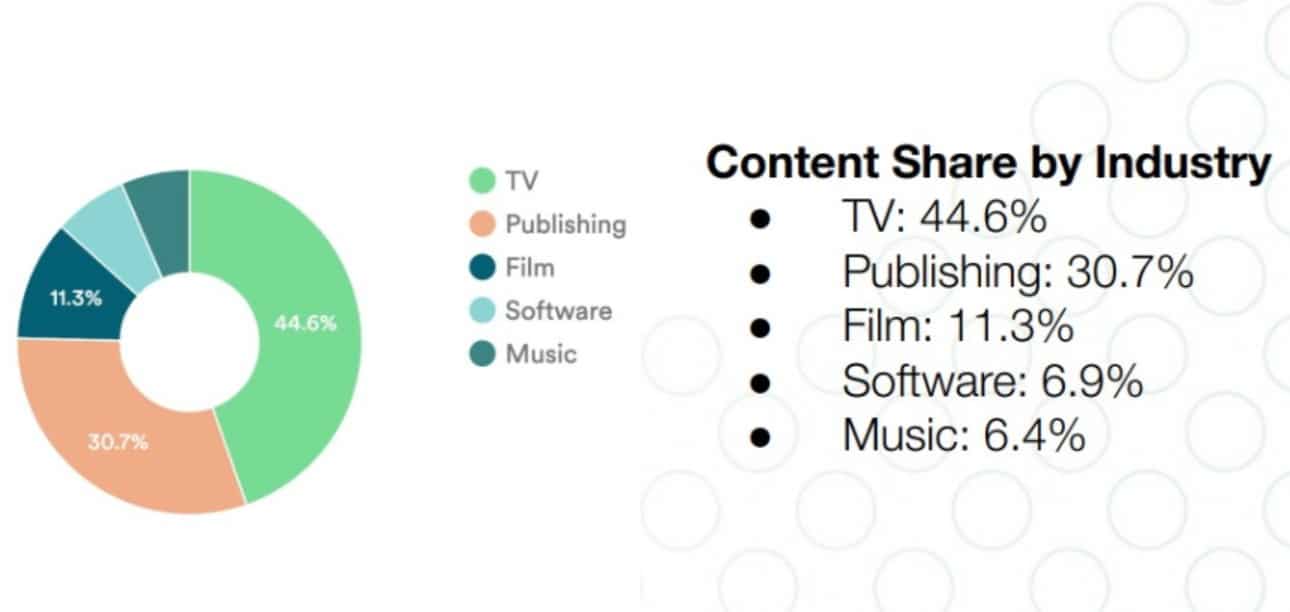

The increase is largely driven by the popularity of manga, which accounts for more than 70% of all publishing piracy. Traditional book piracy, meanwhile, is stuck at 5%.

The increase is largely driven by the popularity of manga, which accounts for more than 70% of all publishing piracy. Traditional book piracy, meanwhile, is stuck at 5%.

In 2006 alone, Russia-based AllOfMP3 reportedly banked $30 million from sales of an unauthorized music product for which the major labels received no payment.

In 2006 alone, Russia-based AllOfMP3 reportedly banked $30 million from sales of an unauthorized music product for which the major labels received no payment.